Associated since antiquity with regality, luxuriance, and the loftiness of intellectual and spiritual ideals, we owe the use of the color purple to a slimy source: minute secretions of mucus from a single species of predatory rock snail.

Tyrian purple, or “royal purple,” was the most prized, prestigious fabric dye of the ancient world. Paradoxically, its contradictory source was a sea-snail of the genus Murex found off the shore of the ancient Phoenician city of Tyre, in modern-day Lebanon.

Just what shade actual Tyrian purple may be debatable, but the HTML code for representing it on you computer screen yields the hue you see here.

The substance had to be distilled from a dehydrated mucous glands that lie just behind the rectums of thousands of the little mollusks. Though exclusive to kings, emperors, popes, and celebrated scholars, for all its lofty connotations, the color came, as an article from the BBC put it, “from the bottom of the bottom-feeders.”

Not even its stinkiness was a deal-breaker: fabric colored with the dye even “long after staining, retained the stench of the invertebrate’s marine excretions.” And it was still more valuable than gold.

Theodoor van Thulden, The Discovery of Purple, 1636, completed from a sketch by Rubens, in which Hercules’ dog discovers Tyrian purple.

No one knows the origin details for sure, but all agree that it began with a dog. The Greeks said that the hero Heracles (Roman Hercules) and his dog were walking along a beach on their way to visiting a nymph. The dog chomped up a snail or two and ended up with a purple mouth. In the Phoenician version, the dog belonged to a Tyro, the mistress of the god Melqart, who named the city for her. When Tyro saw the beast’s stained muzzle, she begged Melqart for a shawl of the same color.

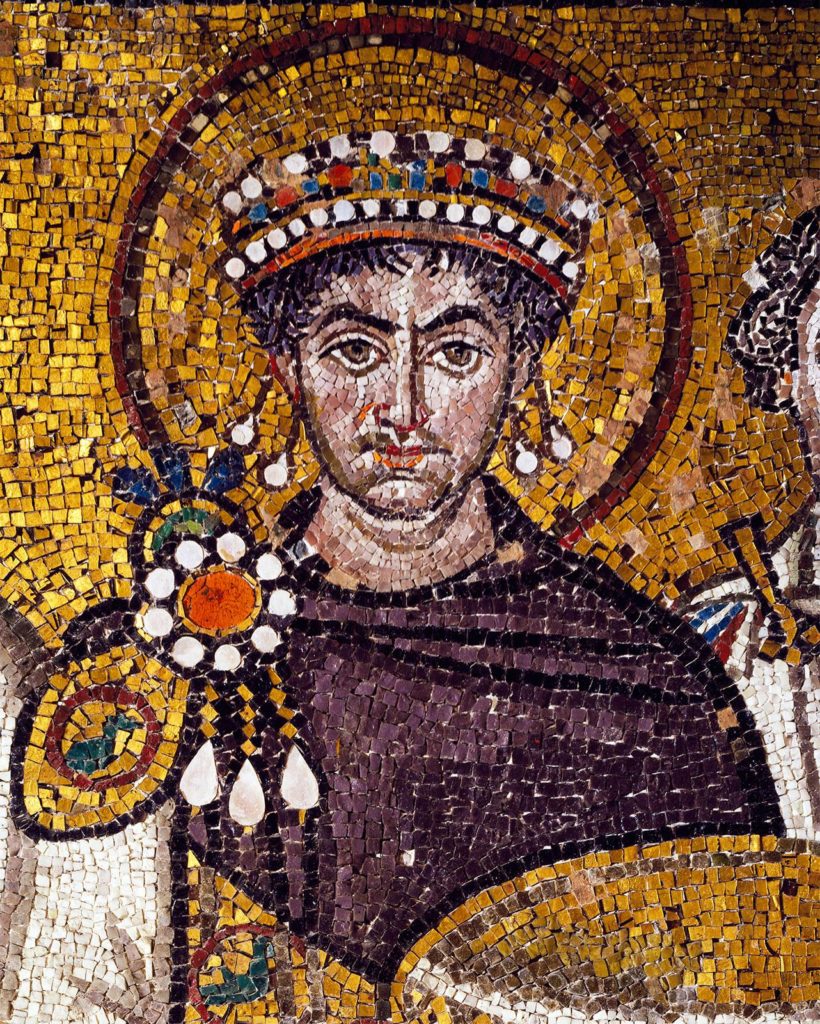

Byzantine Emperor Justinian I clad in Tyrian purple, contemporary 6th-century mosaic at Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy.

The word “purple” comes from “purpura,” the Latin word for the sea snail, as does the name Phoenicians, literally the “purple people.” Huge mounds of broken shells from the dye industry of centuries past are still found near great Phoenician centres.

So costly was the color that the Romans reserved it for elites, whose purple-fringed robes signified the power and wealth of the Mediterranean’s most powerful dynasty. Anyone else wearing a purple toga could get the death sentence. Even today it’s super expensive; purple dye made from the substance sells online for about $2,500 a gram.

One of Tyrian purple’s surprising features is that it doesn’t fade in sunlight but actually deepens instead (a miraculous property at the time). For the ancient Phoenicians, the trade in Tyrian purple helped build a mercantile empire that fueled colonies across the Mediterranean.

At least one contemporary enthusiast is dedicated to recreating the lost art of creating Tyrian purple from the small sea creatures.

It takes more than 10,000 crushed snails to extract one gram of the dye, making it almost priceless. Even today, genuine Tyrian purple oil pigment purchased online will cost you $107 per 25ml (the standard oil paint tube size is 37ml), or $1,115 for 250ml, which is the size of a $10 tube of acrylic.

Bonus trivia: The city of Tyre has been called the “Birthplace of Europe.” According to the Greek mythology Europa, daughter of a Phoenician king, was born at Tyre. Greece’s chief god Zeus abducted her to Crete in the form of a white bull. She became the Cretan empire’s first queen and later the continent of Europe was named after her.

That’s a lot of history for a little sea-snail.

The Abduction of Europe – Noël-Nicolas Coypel III (1690-1734)

“In time,” as the BBC drolly put it, “the arduous task of disemboweling sea snails for their secret would give way to a more salubrious synthetic process.”

In 1856 a young British chemist named William Henry Perkin was researching a cure for malaria when he accidentally discovered an artificial substance that could rival the sheen of Tyrian Purple.

The 18 year-old patented the color as ‘mauveine’ (so-called after the Latin term for the mallow flower, Malva, which has a similar shade), which ignited a fashion craze and gave painters purple pigment in abundance. It was in fact the first synthetic fabric dye – the first substance available for the coloration of textiles that didn’t come from plants or animals.

Professor Charles Reese wearing a bow tie colored with an original sample of Perkins’ “maurine.” CC license.

If you’re fascinated by color and want to learn more about how to master its properties in your artwork, check out some of these DVDs for how contemporary master painters think about and use it.