Spoiler: Not every painting has to have one.

Copyright restrictions prevent me from showing the whole painting (boooo!!), but this section of Jackson Pollock’s Lucifer of 1947 contains the seed of the entire work anyway. There’s no need for a focal point here – the painting is all about the dynamic forces of the looping, organic line and the explosion of scattered color.

Jackson Pollock, Lucifer, 1947 (detail)

So what exactly is a focal point and why would you need one?

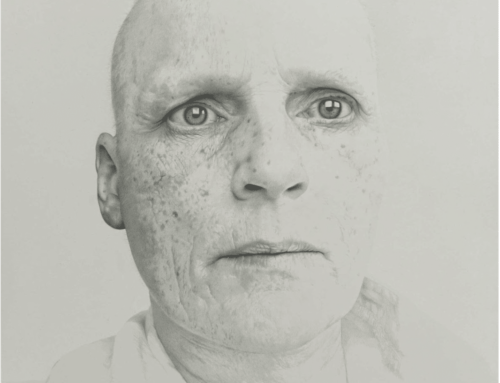

It’s helpful to distinguish between focal point and center of interest. Though these terms are often used interchangeably, a center of interest is that part of a painting that naturally attracts the imagination – it relates to the mind. A focal point is a specific area in a painting that stands out visually from the rest – it relates to the eye. In john Singer Sargent’s Portrait of John Joseph Marie Carrie, the center of interest is of course the model, a young sculptor of the artist’s acquaintance.

The focal point is the strip of white shirt behind his black smock. Pairing high contrast and hard edges in shirt colors like this is a traditional way of saying – HEY! look over here at this face! Rembrandt did this all the time; contemporary artist Eric Johnson explains how to use Rembrandt’s techniques in portrait painting.

In the Sargent, the blacked-out right eye is arguably the (or at least the secondary) focal point – that spot of black in the sea of light-colored flesh certainly attracts our attention, which then immediately travels to the subtler but piercing, point-lit left eye that we can’t take our eyes off). That left eye’s tiny pinprick of light (much stronger in person) and the fleck of light on the eyelid rivet our attention and (because this is Sargent) speak volumes about the model’s intelligence and smoldering creative energy and ambition.

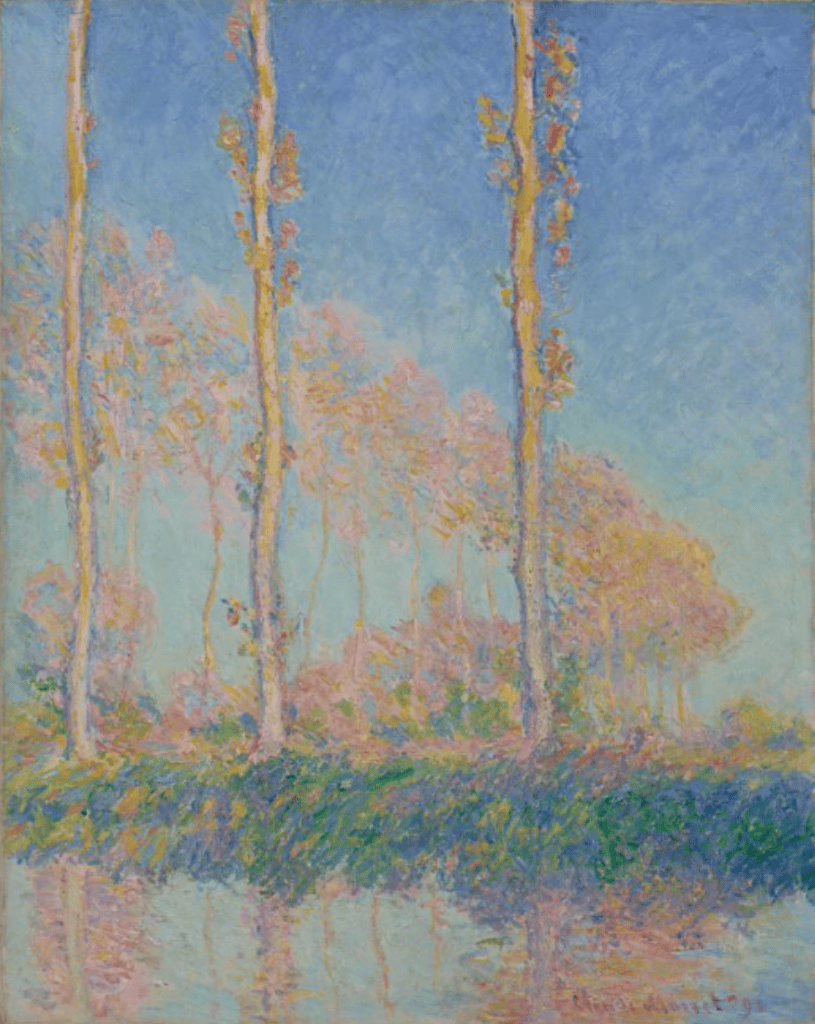

Claude Monet, Poplars, Three Trees in Autumn, 1891

In more atmospheric work, such as Claude Monet’s Poplars series, one avoids focal points – the goal is flow – to immerse the viewer in mood and atmosphere. In the Monet above, there’s no focal point, because the main point of interest is the visual rhythm created between the three trees and the graceful counter-spiral of foliage behind them. Stopping the eye with a single focal point using high contrast and sharp edges would defeat the purpose.

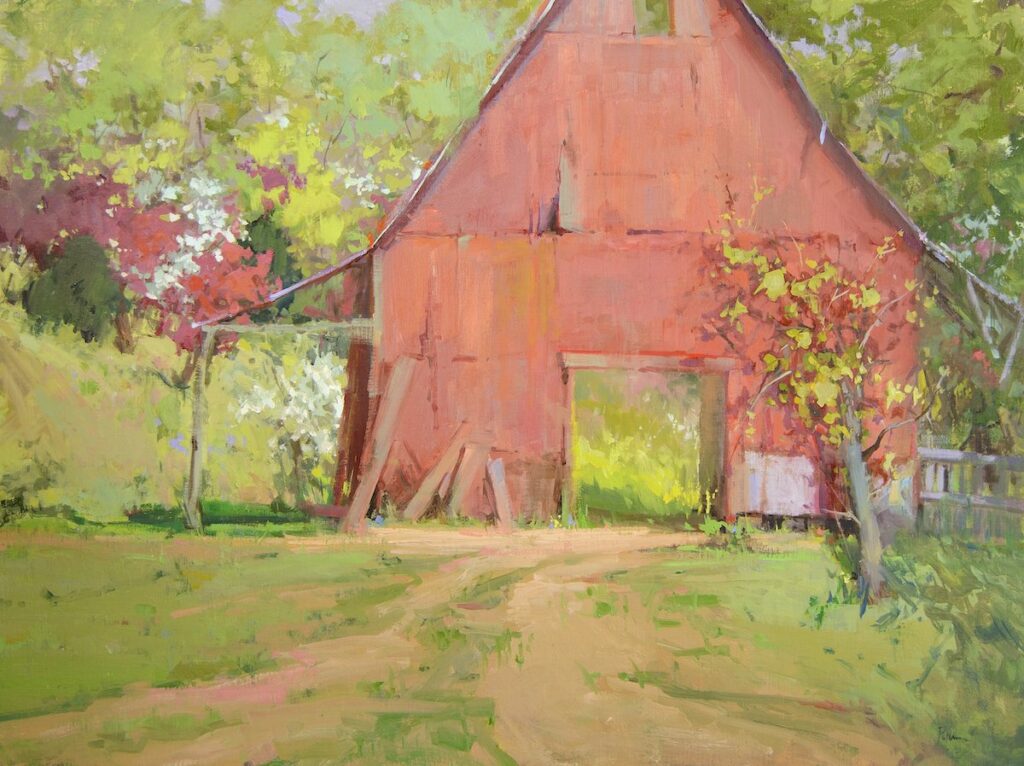

Douglas Fryer, Morning

The same applies to this abstract landscape by Douglas Fryer. Morning suggests the play of natural forces, such as time, wind, and weather. There are multiple “points of interest,” but a strong single focal point would kill the vibe (dude).

A good focal point unifies the composition and enhances the viewer’s enjoyment. A great focal point also drives home the “point” of the painting. It focuses our attention AND the artist’s intention behind making the work. I like the camera lens metaphor. Many all-over-the-place paintings with strong points of interest would benefit from such the anchor of a focal point. Here’s why:

In movies, the director doesn’t just focus her lens on any old thing as long as he or she is following the rule of thirds, unifying the shot, and enhancing the viewer’s visual enjoyment. No, she directs our eyes to something she wants us to look at for a reason – usually because it’s important to the story.

Does every work of art “tell a story?” Some would say yes. A gorgeous landscape, a stunning still life, or an intriguing portrait might not suggest a particular narrative (as in the Sargent example). However, as in the Fryer landscape, they “tell us something” about what the artist saw, felt, and understood about what he was looking at, as well as, of course, what he wants us to see, feel, and understand.

Sensing Place

Lori Putnam, Big Red

“Everywhere I go to paint is my favorite place. It is as if it becomes part of me and me of it.”