“For most artists, incredible windfalls of sales are the exception, not the rule. Most people do ‘good’ at fairs, realizing that event sales are not the only measure of success.”

Some established artists make the bulk of their annual revenue traveling to a handful of high-end fairs where they’re known by a loyal clientele. However, making that model work takes time, experience, ample investment, and lots of dedication to building and nurturing an audience specific to that event. This column of “know-before-you-go wisdom” is not for them, but for those relatively new to the game.

- First and foremost, fairs are a lot of work up front for not necessarily a big reward until (maybe) later down the road.

Artists at the fairs are always asking everyone else how it’s going; that’s because everybody wants to be assured they’re doing all they can to make their significant investments of time and money pay off.

Investment #1 is the cost of participating. Booth fees can range from less than $100 to more than $2000 depending on the fair’s prestige and reputation. It’s no guarantee, but it’s fair (haha) to assume that events with higher fees attract more dedicated, higher-level professional artists. Often the higher end fairs charge fairgoers for admission too, all of which ups the chances of meeting serious buyers as opposed to folks just out enjoying the day. But it’s a chunk of change upfront.

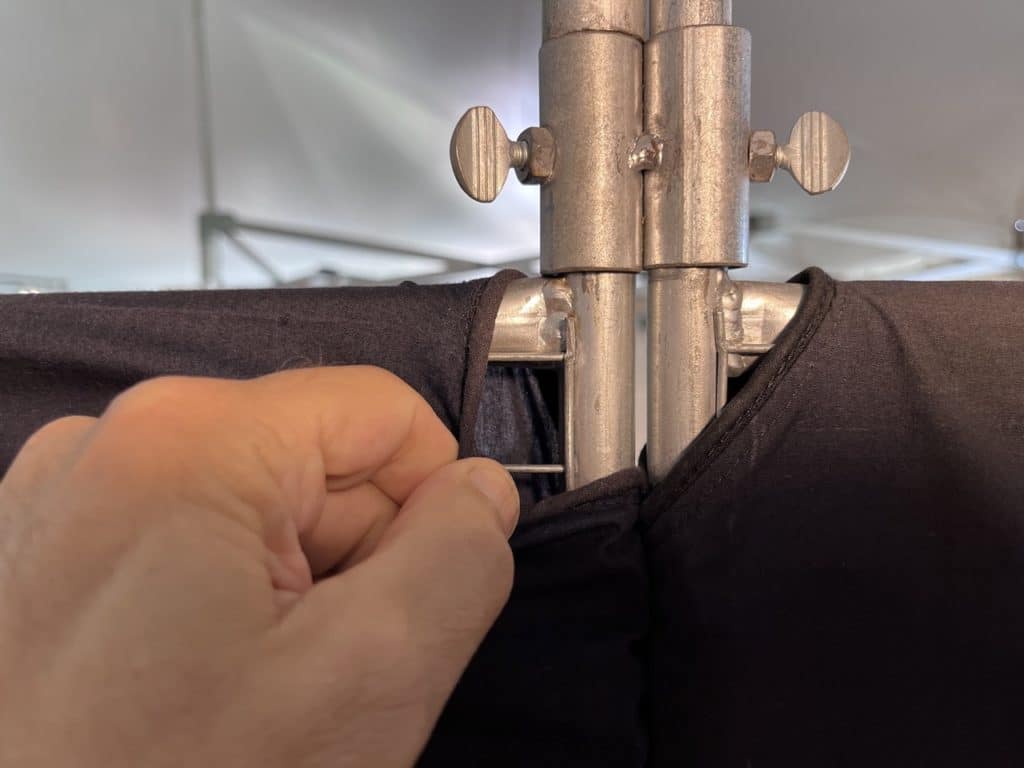

A typical, simple set-up, with fabric-covered racks, photographers’ lights (track lighting is preferable – see below), and an outdoor carpet from the “still good table” at the local dump. Appropriate footwear is recommended (ah-hem).

Sales are uneven and unpredictable. For most artists doing fairs, incredible windfalls are the exception, not the rule. Most people do “good” at fairs, realizing that event sales are not the only measure of success.

Setting up and taking down your booth is huge work, but it’s only the beginning – then there’s working the fair. You cannot just sit there on your phone hoping for buyers. You must engage potential buyers as they approach and enter. That’s a whole different story.

Just know that meeting new potential collectors, making connections with other artists or curators, handing out and collecting business cards and gathering contact emails matters – a lot. In fact, after on-site sales, what happens after the fair is the most important thing. More on this later too.

There are so many unknowns. So, even if you’re a fine-tuned fair-selling machine, doing fairs is generally exhausting, physically and emotionally. The Great Schlepp, I call them.

- You need your own booth. Fairs don’t provide them; the artists bring their own.

If it’s an outdoor fair, you’ll have to have your own pop-up tent as well. So in addition to the event participation fee, you’ll need to lay out some cash for your booth set-up. There are two main schools of thought here: racks and walls. Walls (flat, solid, fit-together panels) you can buy from business conference supply outfits or otherwise make yourself, as many seasoned exhibitors do, out of those hollow doors (sans handle holes) available at home improvement stores.

On the less expensive side, racks are wire-mesh panels that cost around two or three hundred dollars per wall (assuming two-to-three panels to a 10′ wall). Racks look sad unless you cover the wire with fabric. It may be worth getting the fitted covers that pull on over them like a sock leaving the right spaces so the walls can still link to each other.

Wire rack with fitted cover

A 10’x10’ pop-up tent is heavy to transport and often harder for one person to put up and take down than the marketing might lead you to believe. I’d recommend spending more for a lightweight tent that really does go up easy (if you can find such a unicorn). Amazon reviewers are likely your friends here. And don’t ignore what they say about weights; they’re a pain to carry in and out but without them your tent’s at the mercy of the wind. Don’t be “that artist” whose unmoored tent tumbles and crashes disastrously into neighboring booths.

- Tailor your setup to the event (and be prepared to keep working it after it’s over).

Fairs differ considerably one from another. Is it inside a building, under a bigtop, or outside in the open air? If the latter, even without sidewalls, your booth will get hot in the summer sun. Ask other artists where the best spots are, or request a shady spot when you submit your application. You’ll be provided with electricity, so consider bringing a fan.

If you’re going to be set-up beneath a larger tent or anywhere inside, lighting is an absolute must. You do not want to put so much work into this only to have your art look drab and lifeless because you don’t have good lighting. Track lighting (expect to spend $100+) is the best, though you can use flexibly armed architect’s lamps or get by, if you must, with those clip-on reflective metal-hooded lights photographers use (see above).

Two takes on the ten-by-ten: a clean and professional booth on the right, and one on the left so elaborate with glass cases that it might as well be on Fifth Avenue.

If all this sounds like too much and you’re not up for meeting and talking to new people for hours at a time, there are other ways to sell your art perhaps better suited to your temperament. If on the other hand, you like to travel, don’t mind applying some elbow grease when necessary, love the camaraderie of other artists and seeing new people fall in love with your work, then you owe it to yourself to give it your best.

That’s the big picture on what you need to know about fairs. And remember all those business cards, emails, and connections you made? You’ll need to get busy with those and fast.

In future posts we’ll outline strategies for what you should be doing during and especially AFTER the fair, which as I say, is just as important, if not more so, as what happens while you’re there.

Dynamic Reflections

John MacDonald, Reflections of Summer • 24″ x 30″ • oil on linen

A “painter’s painter” is someone other artists admire and look to for fresh ideas and inspiration. Landscapist John MacDonald is one who combines that quality of painting with a flair for teaching.

MacDonald is the sort of teacher who doesn’t offer secrets or shortcuts but rather a deeper understanding of the entire process needed to paint emotionally resonant and visually stunning work that captures charming and arresting nuances of light, color, and surface. His teaching video, Creating Dynamic Landscapes, happens to be available at a generous discount this week.