Sanford Robinson Gifford (July 10, 1823 – August 29, 1880) was an American landscape painter and a leading member of the second generation of Hudson River School artists. A highly regarded pioneer of what’s now known as Luminism, his work was celebrated for its emphasis on light and soft atmospheric effects.

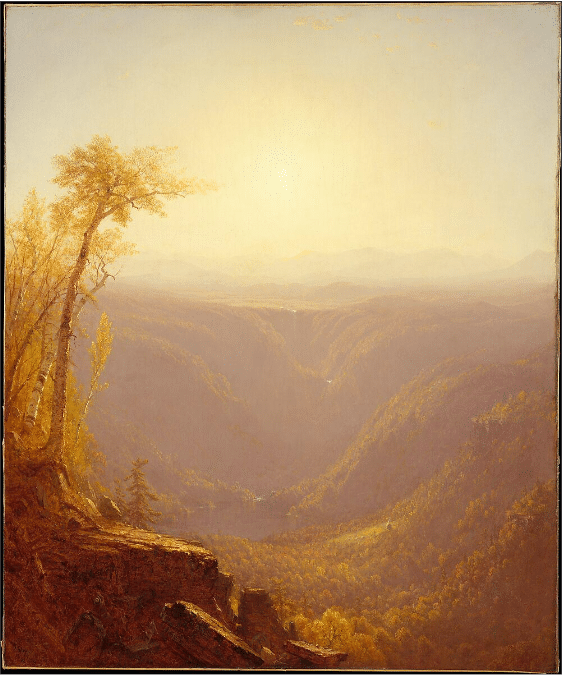

Sanford Robinson Gifford, “A Gorge in the Mountains (Kauterskill Clove),” oil on canvas, 4 ft. x 3.4 ft., (1862)

Gifford’s most important painting is “A Gorge in the Mountains (Kauterskill Clove),” above, which is currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Fifth Avenue Building in New York. In this painting, dated 1862, Gifford achieved an unprecedented dissolution of matter into the immateriality of light.

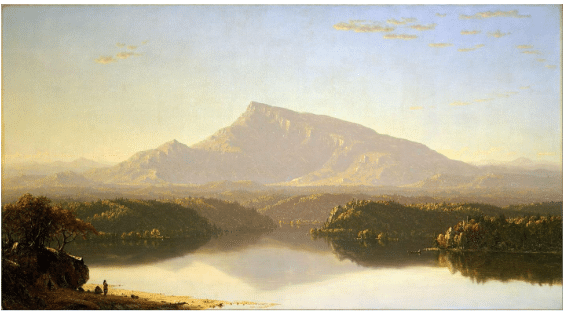

At the time, the convention was to focus on a tree-framed mountain or lake, as did many artists including Gifford on a regular basis. You can see a typical example of the conventional approach in the Thomas Doughty painting from 25 years earlier below.

Thomas Doughty, In the Catskills, 35 ¼ x 45 ¼ in. (1835)

Gifford did many paintings in the Hudson River vein, though he increasingly suffused them with more and more light (witness Gifford’s “The Wilderness” (below), which he finished two years before painting Kauterskill Clove).

Sanford Robinson Gifford’s 1860 “The Wilderness,” oil on canvas, 30 x 54 inc., which resides in the Toledo Museum of Art.

Nature, when approached in solitude with a contemplative mind-frame, invites us into a spiritual relationship with the divine, so thinkers of the time believed (Nature “always wears the colors of the spirit,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson). In 1862’s “Kauterskill Clove,” Gifford visibly infuses nature with light in the same way that Nature as a whole seemed to the Transcendentalist thinkers to embody divinity.

“Kauterskill Clove” fully leans into light and atmosphere. The result is a shift from the sublime or “picturesque” to the meditative. Yet, despite this overall hypnotic, quasi-spiritual effect, the painting is full of concrete detail, both expected and unexpected.

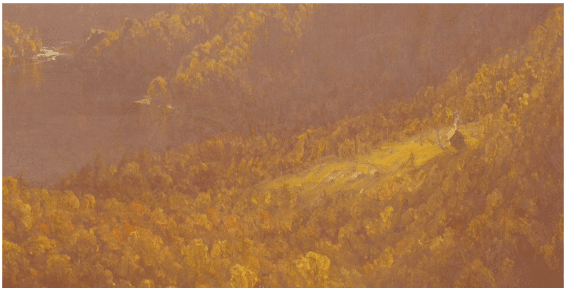

The tiny homestead nestled into the right middle area of Sanford Robinson Gifford’s 1862 painting, Kauterskill Clove (detail).

Gifford has practically rendered every single tree and rock distinctly, no matter how small. There’s a tiny sunlit homestead on one side of the basin, with smoke wafting out of a chimney, complete with minuscule boulders dotting the cleared lot. (See closeup above.)

As if part of the landscape itself, a hunter and his dog can be seen climbing the rockface in Gifford’s painting.

In the left foreground, a hunter and his dog climb the rocks. Barely visible in the image above, they merge with the terrain as they make their way to the platform overlooking the ravine, which is burnished by an Indian summer haze.

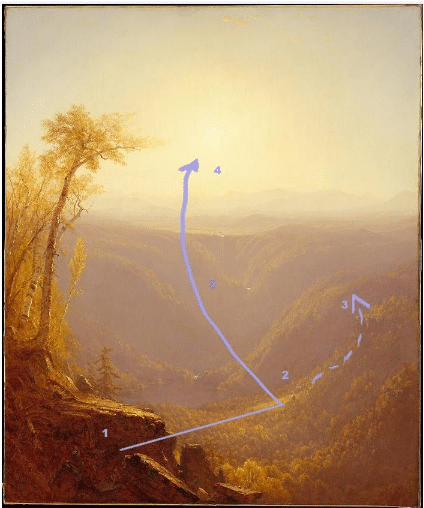

If we begin viewing the painting there, with the hunter close to us in the left corner foreground (#1 in the diagram above), we next telescope our way through the air, as it were, to the distant homestead on the right (#2 above).

Moving through Gifford’s painting.

From there our eyes naturally progress (one way or another) across the distance to the center of the painting and inevitably rise into the soft explosion of the sun, which dominates close to half of the composition.

Why We Should Care

This is an exquisitely rendered and detailed landscape that’s also a marvel of warm, luminous light. It’s among the few realist landscapes undeniably infused with a spiritual feeling for nature. There’s no other painting quite like it.

If we really take time to look, paying attention to the details and hints that Gifford planted for us, our gaze moves from 1. primal human being in his “wilderness state” (foreground hunter and dog) associated with the base, material world, on to 2. the domestication or taming of nature (the homesteader with a clearing in the wilderness), representing the human living in harmony with nature, to 3. the pure celestial, immaterial radiance of the Divine which infuses the scene as with a blessing. One can see this as something of a visual map of the transcendentalist philosophy so popular at the time.

You can explore the painting yourself in minute detail via a high-resolution image hosted by the museum’s website here.

How They Did It

A year before the artist’s death, the art writer George William Sheldon published this first-hand account of Gifford’s method:

“Mr. Gifford’s method is this: When he sees anything which vividly impresses him, and which therefore he wishes to reproduce, he makes a little sketch of it in pencil on a card about as large as an ordinary visiting-card. It takes him, say, half a minute to make it; there is the idea of the future picture fixed as firmly if not as fully as the completed work itself. While traveling, he can in this way lay up a good stock of material for future use.

The next step is to make a larger sketch, this time in oil, where what has already been done in black-and-white is repeated in color. To this sketch, which is about twelve inches by eight, he devotes an hour or two. It serves the purpose of defining to him just what he wants to do. He experiments with it; puts in or leaves out, according as he finds that he can increase or perfect his idea. When satisfactorily finished, it is a model of what he proposes to do.

He is now ready to paint the picture itself. When the day comes, he begins work just after sunrise, and continues until just before sunset. Ten, eleven, twelve consecutive hours, according to the season of the year, are occupied in the first great effort to put the scene on canvas. He feels fresh and eager. His studio-door is locked. Nothing is allowed to interrupt him.

When the long day is finished and the picture is produced, the work of criticism, of correction, of completion, is in place. Mr. Gifford does this work slowly. He likes to keep his picture in his studio as long as possible. Sometimes he does not touch the canvas for months after his first criticisms have been executed. Then, suddenly, he sees something that will help it along.

I remember hearing him say one day, in his studio: “I thought that picture was done half a dozen times. It certainly might have been called finished six months ago. I was working at it all day yesterday.” But one limitation should be noted here. Mr. Gifford does not experiment with his paintings. He does not make a change in one of them unless he knows precisely what he wishes to do. When Mr. Gifford is done, he stops. And he knows when he is done. Yet, on the other hand, he would rather take the risk of destroying a picture than to feel the slightest doubt respecting any part of it. The moment of his keenest pleasure is not when his work is satisfactorily completed, but when, long beforehand, he feels that he is going to be successful with it.”

Erik Koeppel, The Heart of the Wilderness, oil, 34 x 46 in.

If you’re interested in learning how the Hudson River painters made their paintings and trying your hand at the style, you might want to check out this bundle of two videos by the living exponent of the manner, Erik Koeppel.