Theory: What happens in the first 15 minutes makes or breaks a painting.

Hours and days of fixing details and adjusting colors or values will not undo a weak or deficient start. Fussing will only become overworking if the underlying design or initial lay-in ain’t got that swing.

Apple Still Life by Douglas Fryer (Meyers Gallery). Fryer advocates a spontaneous painting approach, building off his longtime use of a geometric armature underlying his compositions.

If there’s any time to get out of your own way, this is it. What you need, besides an initial Idea for the painting that excites you and a firm grounding in composition and design, is confidence. Painting intuitively benefits from the “learn the rules and then forget them” approach.

Lacking that, brazen devil-may-care abandon can work wonders at the outset! Just remember to step back and take a critical look and make any needed adjustments before you get too far in.

Robert Henri, Portrait of Faith, 1927

The degree of finish or draftsmanship is irrelevant here. We might be talking about beginning with, on one hand, a loose underlying sketch, or on the other, a detailed drawing; a careful block-in of the big shapes and values, or the wild-at-heart dashing-in of full notes or fields of color and texture. The issue isn’t realism vs. abstraction, and it isn’t about measured line-drawing vs. gestural mark-making; style is secondary to seeing big and not second-guessing a thing.

Carlos de Haes, Los Picos de Europa, 1876

Starting a painting is one of those things where it’s better to dive right in. Fifteen minutes later, once it’s on the canvas, you get to stand back and assess and adjust your initial design before going forward. It’s good to start a painting with a general idea or “vision” in mind for the completed work, but it’s okay to mentally keep it vague and provisional, subject to change – as long as you know your destination, it’s okay not be sure how you’re going to get there.

Inspire yourself: It’s also fine to let go of that vision completely if the painting takes off in its own direction (not arbitrarily though – before you take a major side road, it’s best to have a new vision of an equally exciting painting-in-the-making to be inspired by).

Jan van Goyen, Dune Landscape, c 1634

As far as keeping a painting fresh to the end, the secret is never losing sight of the reason for starting the painting in the first place. As Charles Hawthorne says, “that first excitement, that one big relationship. If the details slowly obscure the big thing, the painting becomes dull.” It may be possible, if you catch it soon enough, to dig back in and pull that “first excitement” back out, but it’s better to catch the breeze at the beginning and just keep turning the sails before the wind dies.

So how to save yourself the headache of tickling your paintings to death? One good answer, as Hawthorne taught, is to make lots of starts. When you get a good one, something with some life and promise, try carrying it only as far to completion that it needs before it starts to lose its sparkle. Then move on to the next start – that one’s done.

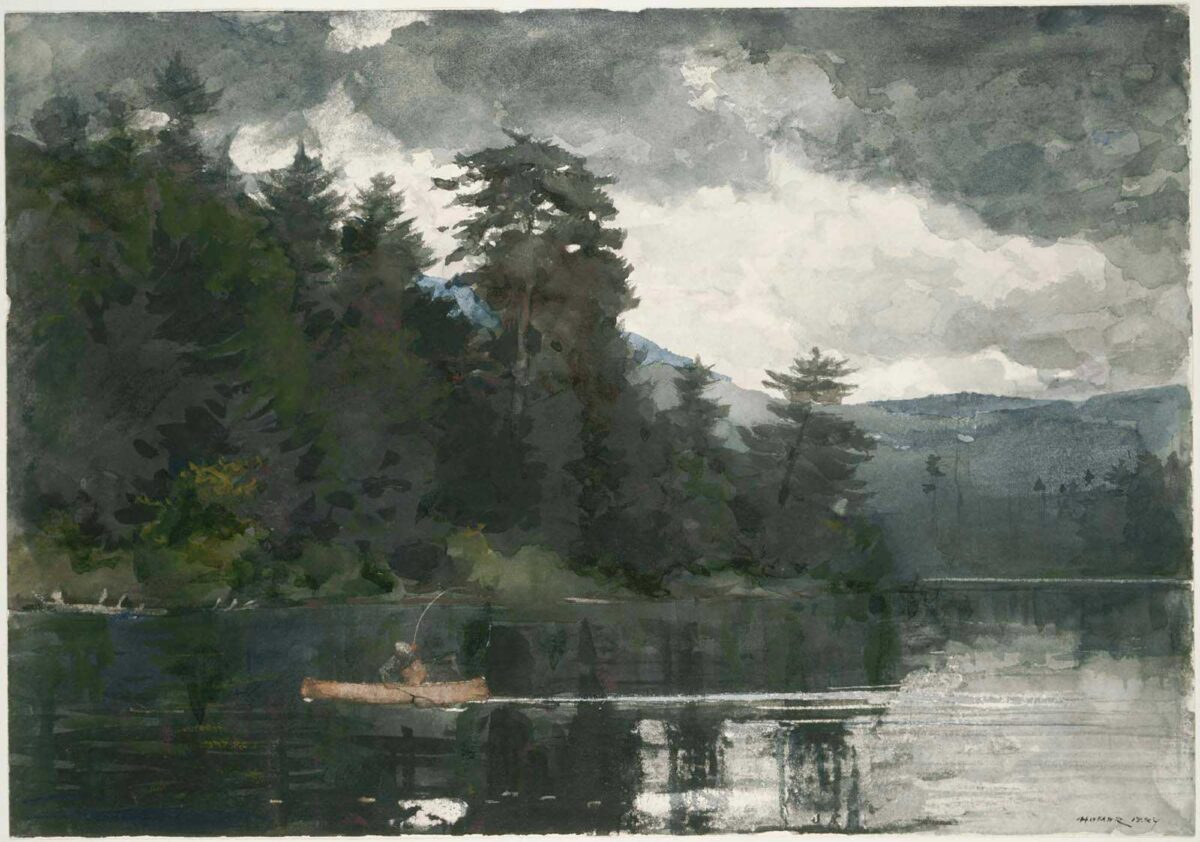

Plein Air Painters Flock to the Adirondacks

Streamline Publishing’s Eric Rhoads goes at it. Rhoads runs the popular annual gathering, which takes place in a different scenic location each year.

Dozens of plein air painters from all over New England and many parts of the country have descended en masse upon the beautiful mountains and pastures of the the Adirondack Mountains of Northern New York State. They’re there for the 11th annual “publisher’s invitational” as it’s called (even though everyone is invited to join the bunch).

It’s great to see that a favorite spot for the artists of the Hudson River School continues its rich history of drawing artists to the beauty of unspoiled nature.

In the paint,

Chris