Landscape painters often say their paintings capture “a sense of place.”

It’s an intriguing phrase when you think about it. It’s most often understood to mean that, in an age where cameras can (and do!) record everything around us, the artistic goal is to capture the sense or “essence” of a place.

The “sense of place” requires that, on some level, the artist mentally “enters into” and expresses the characteristics that define that locale. An “essence” is a distillation, a concentration of a thing’s defining qualities. But how do you make a viewer care about the “essence” of a place – the quintessence of Albuquerque, let’s say – if they have no personal connection to it, if they don’t live there, or at least vacation there? How often do evocative light, atmospheric conditions, particular times of day or night take precedence over which state of the union we’re in? How much of landscape painting is really about the artist’s sensibility instead of the place?

Because sometimes, the complete opposite can be true: some of the best landscapes emphasize perception as well as, or even more than, place. Such artists are “looking” beyond the particular in search of something universal, something a viewer can sense, see, and feel through the painting, regardless of the place depicted.

And many landscapes transcend any sense of place altogether. A strong landscape untethered to the essence of any one locale can express something of the artist’s being, drawn out, perhaps, by the artist’s experience within that geographical location but not tied to it.

Some of the world’s greatest landscapes express spiritual and emotional responses, not to any one place but to Nature and life itself. Think about Claude Monet, JMW Turner, or George Inness – those artists all titled a good number of their paintings after the locations where they lived, painted, or sketched. But how much do those place names relate to why we love the work?

Monet’s garden is famous not because of how awesome it was but because of how Monet painted it.

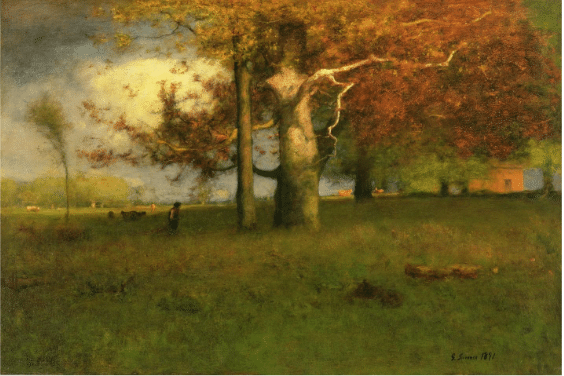

George Inness, Early Autumn, Montclair, oil (1891)

Or take George Inness for example. Inness certainly referred to the place he lived, namely Montclair, New Jersey, in plenty of his paintings’ titles. But what we get in a landscape by Inness is not, in fact, the sense or essence of a single rural town in New Jersey.

What we get has less to do with “place” at all and more to do with Inness; his works sing because of how he painted, not what he painted.

Inness’ landscapes, such as Early Autumn, Montclair (above), evoke thoughts and feelings in the viewer that have little to nothing at all to do with the location depicted. Does labeling the painting with a place name mean Inness needed the anchor of place before he could paint the larger things he “saw” and felt through his perception? Inness believed in a theory of “correspondences” between things on earth and things in Heaven; does he mean for his title to imply that anywhere (as in “even, for example, Montclair, NJ”) is worthy and capable of reflecting beauty and the divine?

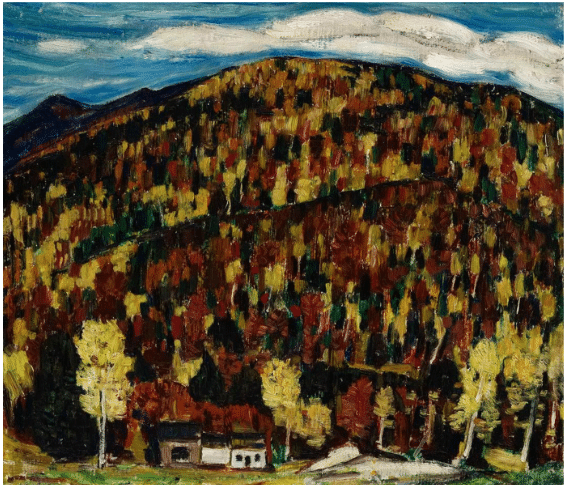

Marsden Hartley, Maine Landscape, Autumn No. 13, oil, height: 29.8 cm (11.7 in) ; width: 34.3 cm (13.5 in), 1909

There’s an essay that touches philosophically on some of this by Jordon Wolfson titled “How Painting Can Help Save the World, Actually.” Here is a quote from Wolfson’s essay:

“When we paint, we have the possibility of bringing ourselves into the work—bringing our life force into the mark, the material, bringing our actual being, in this very moment, as it is, into our touch and setting free that vibration and energy.”

“What if painting, actually, is about the interaction between two minds, two hearts, two beings—the painter and the viewer? What if painting is about a way of coming to the world, a kind of communion?”

“Place is not a static mental or perceptual construct converted to paint and canvas,” Says Marsden Hartley scholar Gail R. Scott. Place is the vehicle by which the artist moves out from his own creative center to discern the universal truths of man and his environment.”

By that definition, place matters plenty – not for the reasons we think and say it does, but for reasons more mysterious and marvelous still.

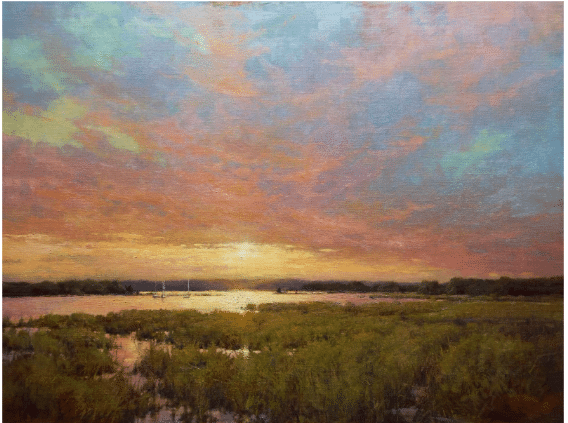

Cindy Baron, oil

If you’re interested in learning to put more of yourself into your landscape paintings without “going out of the lines” of the observable world in front of you, consider the video from Cindy Baron titled Elegant Landscapes.

Cindy’s demonstrations of technique are as practical and thorough as they get. Yet Cindy’s paintings are full of imagination, emotion, and style. She recommends starting with a picture in your mind of the finished painting and then working backwards through a sketch or a photo. You’ll learn how to “see” in a whole new way. And you’ll learn the techniques to transfer it to the canvas to create an unforgettable painting that balances detail rendering with personal artistic expression.