“Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting—

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.”

– Mary Oliver

Mary Oliver’s poem Wild Geese speaks, to me anyway, about the creative life.

The poem, reproduced below, starts out, “You do not have to be good.” Right away you know this is coming from a place of total acceptance and the gifts and “permissions” that non-judgment brings. For me, reading specifically from the point of view of a maker of art, this alone resonates with the promise of a joyful creative freedom. You are enough, it says. Whatever you make, keep making it. Making is good.

We’re all lonely, scared, needlessly self-punishing little things, and art is one of the things we hope will make us whole – and it can, even if that’s only for brief intervals. “Meanwhile the world goes on,” Oliver writes, the cosmos of earth and sun do what they do, “moving across the landscapes… over the mountains and the rivers.”

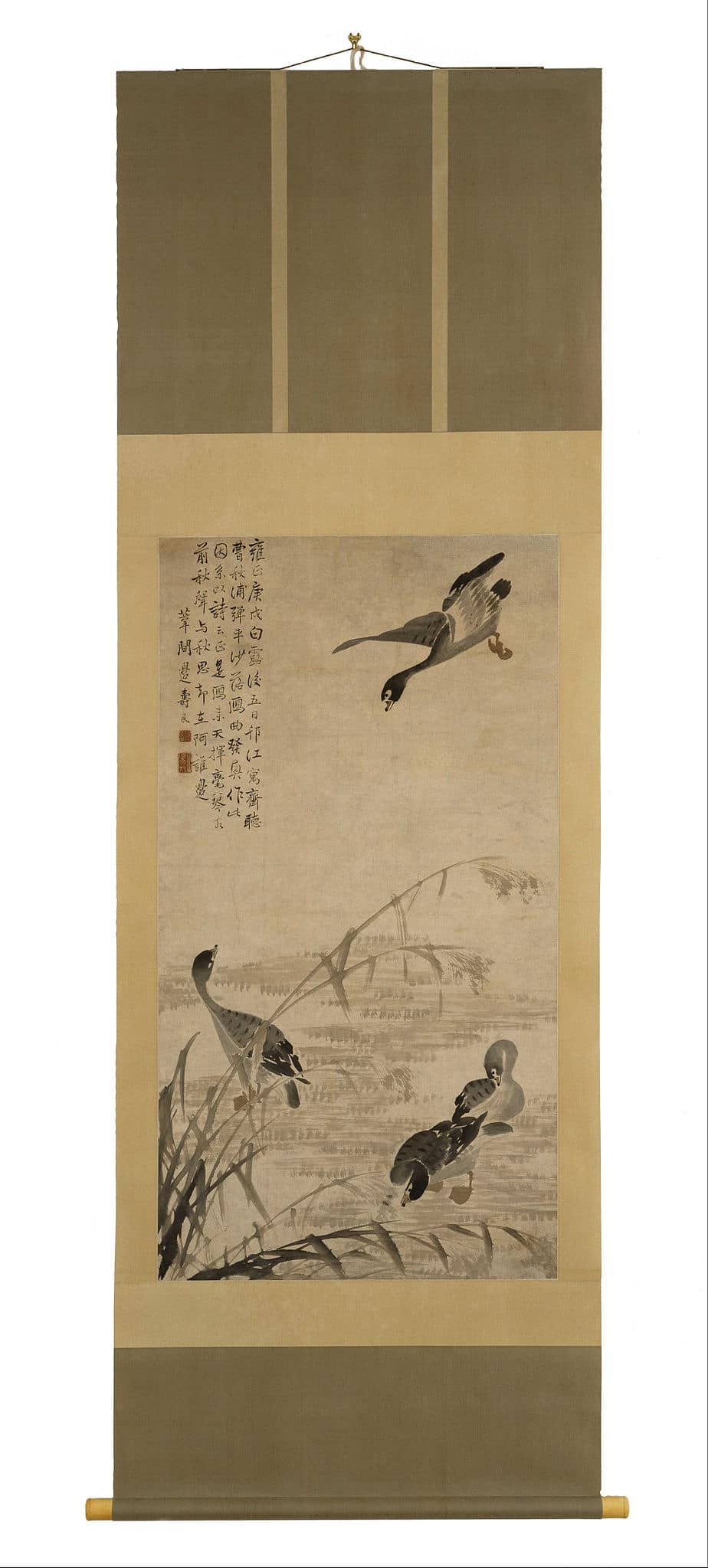

Geese Descending on a Sandbank, By Bian Shoumin (also, Weijian Laoren or Yigong, 1684–1752). Geese are very important in Chinese poetry. Bian’s inscribed poem reads:

Just now wild geese came into the sky,

As I waved my brush before the master of the qin [zither];

Autumn sounds meld with autumn thoughts

As I stand beside I know not who.

It’s spring, a time of new beginnings and a time of homecomings, as “the wild geese, high in the clean blue air, and heading home again.” What is it we hear in their “harsh and exciting” calls, what message do they “announce” for us? It is that we are all already home. We have everything we need to be fully alive, and everything we need to make our best work is available to us, if only we can find the inspiration to embrace it.

Frank W. Benson, Canada Geese in Formation

“Wild Geese” reminds us that we are “part and parcel” (as another American poet, Walt Whitman said) “of the God (or whatever your personal sense of the divine or the sacred – cv) that radiates out from us to the far reaches of the cosmos.”

It’s still, as it always has been, the place of the creative arts to touch that truth and inspire us all to carry it on.

Wild Geese

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting—

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

Mary Oliver

From: Devotions

By the way, there is a brief but great and much broader appreciation of this beloved poem, as well as a link to Mary Oliver reading it over here.

Cleveland Museum Acquires Powerful Bust of Enslaved Woman

Jean-Baptiste Carpeau, Why Born Enslaved!, 1868 Picture: Cleveland.com

The sculpture is powerful and striking all on its own, but the stories tied up in it are just as meaningful and intense, as this statement from the museum suggests:

“The Cleveland Museum of Art sees its new acquisition of a major 19th-century French sculpture expressing abolitionist outrage against slavery as a launchpad for wide-ranging discussions on the role of politics, race, and power in art history — and in the history of its own collection.

The plaster sculpture, entitled “Why Born Enslaved!” created by the artist Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux in 1868, is a bust-length portrait of an anonymous enslaved Black woman, bound tightly with ropes, with her gown ripped away, revealing her left breast. […]

The acquisition of the Carpeaux comes as cultural institutions across the U.S. are re-evaluating racial equity practices in the wake of the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020, and the national wave of Black Lives Matter protests that followed.

The Cleveland museum, which serves a city that is roughly 50% Black and is surrounded by low-income, majority-Black neighborhoods, adopted its first Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Plan in 2018, and over the past decade has stepped up the frequency and scale of exhibitions and purchases of works by African-American artists.

The bust, of which there are a number of versions in different media, was originally modelled as part of a commission for the Fontaine de l’Observatoire in the Jardin de Luxembourg in Paris. It was intended to represent Africa, which, along with representations of Europe, America and Asia, held up the world. Carpeaux’s initial designs drew some scorn, and in the finished fountain the full length figure of Africa is more idealised, and bound only by her ankle.”