“If you look at art history, at Goya or Gainsborough, it’s always about acknowledging the people of your time who have influence.” – Sam Taylor-Johnson

No artist, contemporary landscapists included, should work in a vacuum; your work will be both stronger and more interesting to you for knowing what’s been done and why (the motives behind it).

I’m calling this a “history of art,” but it’s really the opposite; it’s an obviously incomplete account of landscape that along the way illustrates a few of the art’s different roles in history. It begins in ancient China and ends in 21st century Germany and New York.

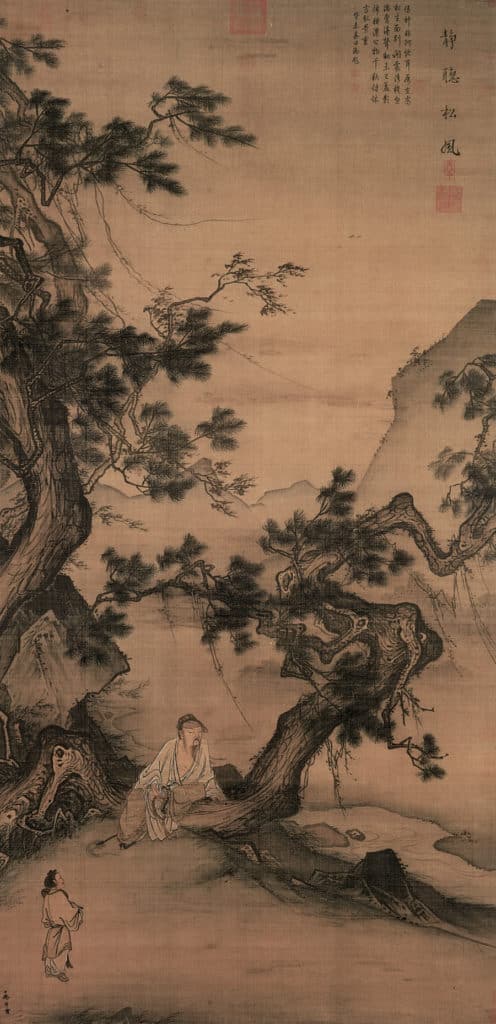

The Mystic’s Grove: Chinese Landscape Painting

Many consider Chinese landscape painting one of the most mesmerizing and beautiful arts in the world. Chinese artists intended their creations to be almost magical objects; meant for private contemplation, they were portable silk scrolls showing nature as full of meaning, spirituality and mysticism. Therefore their landscapes were often visionary and imaginative rather than real places.

Unlike Western painters, Chinese landscape artists used the stroke, not color, as well as composition and line, as the primary expression of their essence and vision. The search for meaning through a faithful mimetic representation of visible reality is left behind as beside the point.

Ma Lin, Listening Quietly to Sighing Pines, ink and color on silk, 13th Century before 1246

The Merchant’s Vast Domain: Dutch Landscape and the “Pastoral” as Product

How different is the role of landscape painting in Europe when the Dutch “old masters” depicted the domains of their wealthy patrons.

During 14th – 17th century Europe, a rising Dutch merchant class flush with new money rushed to fill their newly rising townhouses and country estates with art that flattered their self-image and reflected their worldly success. The art of oil painting, relatively recently perfected by the Dutch, proved just the thing.

Jacob van Ruisdael, Wheat Fields, oil on wood, 1670

Jacob van Ruisdael painted the landscape titled Wheat Fields in 1670, at the height of Dutch prosperity. Here, unlike in Chinese landscape painting, it had to be a “faithful” representation of a specific location. The wealthy businessman who commissioned this painting owned these fields and surely would have gazed with satisfaction upon this image of his successful commodity crop.

A glimpse of tiny boats at sea on the far left is intended to reference the unrivaled strength of Dutch shipping and its dominance of the maritime trade routes over which Dutch goods, such as this sun-spotlighted wheat, could be shipped abroad.

Detail from Ruisdael’s Wheat Fields showing distant commercial shipping vessels

This would have been painted as a commission for the merchant who owned these fields. Giving so much space to the sky in this painting does two things; it imparts a feeling of grandeur and nobility to what after all is commercial farmland, and it literally shines a benevolent, even divine spotlight on the cultivated fields that stretch (humbly by contrast) below the billowy dome of Heaven.

Extra Credit: The Pastoral Landscape

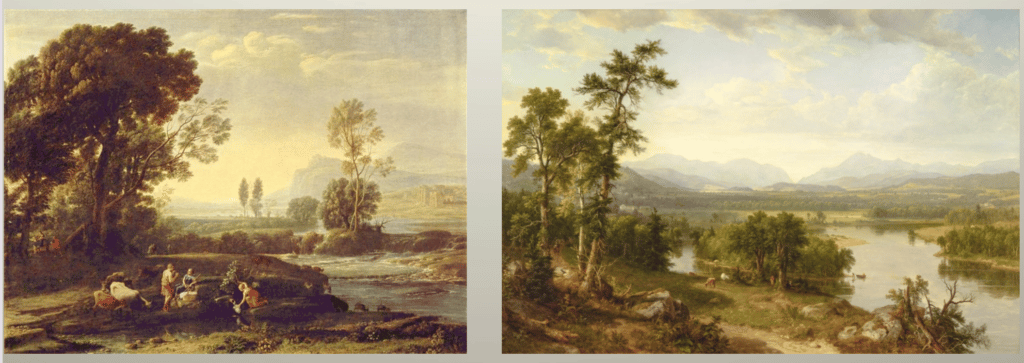

For several hundred years, the landscape paintings purchased by European elites (meaning anyone who wasn’t connected with the Church) were decorative objects intended to demonstrate wealth. They kept closely to a formula developed at the tail of the Renaissance by the French Academy at Rome called the “pastoral” landscape.

Claude Lorrain, Pastoral Landscape: The Roman Campagna, oil, 1639.

Almost always they show a combination of the same elements: a few low mountains receding into the distance, a body of water, and hilly pastures (hence “pastoral”) with imaginary classical scenery (little Greek or Roman ruins dotting a peaceful land of plenty peopled in the foreground by dreamy shepherds and comely country maidens, all framed on left and right by leafy backlit trees on either side of the canvas. Variations of this composition provided the scaffolding of landscape painting all the way from 1600s Europe well into 1800s America.

Left: Claude Lorrain, 1647 / Right: Asher B. Durand, 1860

Although thousands of such paintings still hang in old estates, villas, and castles, with the finest examples in museums all over the world, they’re all pretty much the same, and we shall have much more interesting work to look at in the following installments of this series.

Left: Claude Lorrain, 1650 / Right, Thomas Cole, 1840. There’s a whole different post to be written about this.

P.S. On a personal note, I think it’s a travesty that 9 out the 10 quotes selected by the algorithms on “BrainyQuotes.com” (when you search “quote importance of art history” on Google) are basically anti-brainy, anti-intellectual, empty arguments for the non-importance of art history and, tellingly, almost NONE of them are by actual acclaimed visual artists. Thanks, American Internet(TM).

In the paint,

Chris