It’s said the triangle is the most stable of geometric forms. It’s the most heavily weighted in terms of base vs. height, and therefore is said to evoke stability and balance, a sense of assurance and calm. This is a function of the equal distribution of visual weight. (The forms in any given composition have a certain “weight” in terms of how they “call the eye” from one to another.)

In a pyramidal or triangular arrangement, either forms assume the shape of a three-sided figure or visual weight is more or less evenly distributed among various elements that definitely relate to one another in a triangular, or triadic, arrangement.

Having three sides, the pyramid or triangle seemed a natural choice for Christian art; in church commissions, the trinity of the Holy Family motif found visible form in three-sided geometry. Furthermore, with its pinnacle pointed toward Heaven, the pyramid or triangle also suggested aspiration toward the Divine paired with the stability of the Church on earth.

Renaissance painters like Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael and later history painters used it repeatedly for their Madonnas and Christs on the cross.

Stability & Majesty

Palm Vecchio, Holy Family with St. John

In Vecchio’s Renaissance painting of the Holy Family, the triangle assumes an unusual off-center position in the overall composition and yet maintains a powerful sense of stability and even majesty, as the composition elevates the holy mother Mary and the infant Jesus above the rest of the figures paying homage.

As a compositional device, the triangle or pyramid brings with it a kind of built-in self-containment. It’s a satisfying underlying design, as the eye goes up and down and around the three sides over and over again, without ever being led outside of the frame.

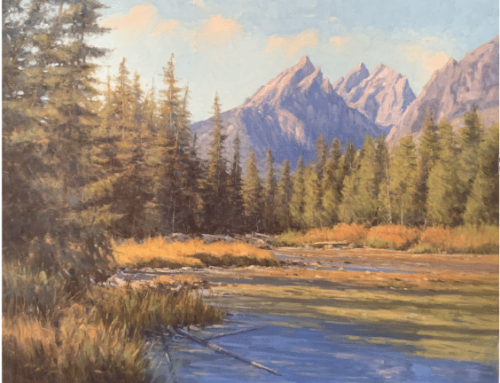

It’s a favorite of floral and other still lifes, landscapes with groves or bunches of trees, and, after Leonardo employed it in the Mona Lisa, it became central to portraiture and still is today.