Born to a wealthy Parisian family, Jacques-Louis David (pronounced dah-VEED) was only seven when his father was shot dead in a pistol duel. Brought up by his late father’s brothers, all he wanted to do was paint, and he was eventually sent to his mother’s cousin, Francois Boucher, the most successful painter in all of France at the time.

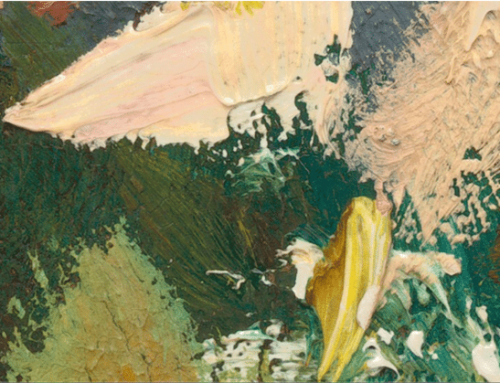

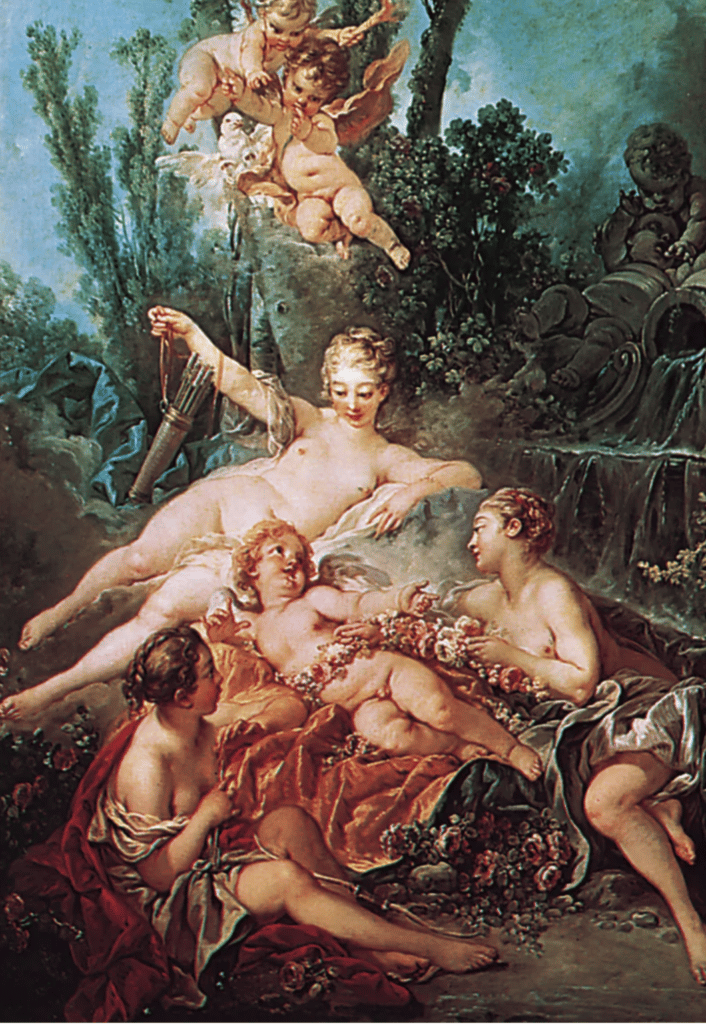

Francois Boucher exemplified the height of the prevailing fashion in painting: art for the aristocracy, a trendy, elaborate, and elegantly refined style favored by the royal tastemakers, such as Louis XV’s powerful and influential courtier Madame de Pompadour. The pre-Revolutionary Rococo style, as it’s known, was over-the-top fancy, exceedingly pleasant, and decoratively erotic.

Francois Boucher, Cupid a Captive (detail), oil on canvas by François Boucher, 1754; in the Wallace Collection, London. 164.5 × 85.5 cm. Courtesy of the Trustees of the Wallace Collection, London; photograph

David was a quick study and turned out accomplished works in Boucher’s Rococo style. But things happened in David’s life that made him detest the Rococo style for its superficiality and its blatant celebration of the spoils of privilege. The Rococo, he came to feel, was out of step with the reality of the times, just like the decadent royal court who patronized it, and to which the violent uprisings of the French Revolution were about to put an abrupt end.

Maquette of a posthumous bust of David by François Rude, 22.5 cm. High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Painting for David became an important means of communication after his face was slashed in a fencing accident and his speech, already affected by a stammer, became embarrassingly distorted by a benign tumor that developed from the wound.

With a much more serious and introspective lease on life than Boucher, David looked in an opposite direction from his master and developed a new and severe classically influenced style.

David’s style departed from the frivolity of the Rococo period and reflected the moral and austere climate of the years leading up to the French Revolution. The movement would come to be known as NeoClassicism.

It’s as though the disorder of his face were to be cancelled out by the classical beauty and poise, the extreme gravity and flawless beauty, inherent in this new approach to “historical painting.”

David became closely aligned with his patrons in the new government, and his work was increasingly used as propaganda. The Death of Marat (1793), an idealization of the violent assassination of a radical political figure, proved his most controversial painting.

“If there’s ever a picture that would make you want to die for a cause, it is Jacque-Louis David’s Death of Marat,” says art historian Simon Schama of this work. “I’m not sure how I feel about this painting, except deeply conflicted. You can’t doubt that it’s a solid gold masterpiece, but that’s to separate it from the appalling moment of its creation, the French Revolution. This is Jean-Paul Marat, the most paranoid of the Revolution’s fanatics, exhaling his very last breath. He’s been assassinated in his bath. But for David, Marat isn’t a monster, he’s a saint. This is martyrdom, David’s manifesto of revolutionary virtue.”

This is a picture of a man who’s just been stabbed to death in a bathtub. It’s very unlikely that a virulent political dissident expired quite this placidly, with a beatific smile on his face, set glowing by a warm ray of light, quill pen still upright in one hand and notes for his next political essay held up in the other. David is doing something quite different from realism here.

Note the similarities of the Marat painting to David’s equally imaginary NeoClassical portrayal of the death of Socrates. Surrounded by his mournful pupils, the great philosopher expounds on why he is about to end his life by deadly poison rather than be forced to dishonor his noble devotion to Truth.

Here’ how they exemplify the NeoClassical period style: They both offer an artificially shallow pictorial space, a device that likens them to the horizontal “frieze” tradition of classical Greek sculpture reserved for great historical events and mythological figures.

David’s Marat and Socrates both transform momentous events (one contemporary and one ancient) into near mythological status and inject them with moral idealism. David’s figures, like ancient classical sculpture, demonstrate “a noble simplicity and a quiet grandeur, both in posture and expression,” as 18th century German tastemaker Johann Winckelmann put it.

David, then, is saying that Marat is a heroic figure, one of the great martyrs to justice and truth in history, whose tragic sacrifice bears a dignity worthy of timeless immortalization for the ages. How utterly unlike the soft and frilly self-indulgent Rococo style of Boucher above!

The course of art distills human history over time. Indeed, history remembers such figures as Marat partly because great artists depict them so unforgettably. And in the process, artists with far-sighted vision, such as David, often make history of their own.

NeoClassicism remained the “official” painting style of the French Academy and the Salon for the next hundred years, until the challenge of Impressionism and, shortly after, the all-out earthquake of modernism and abstraction.

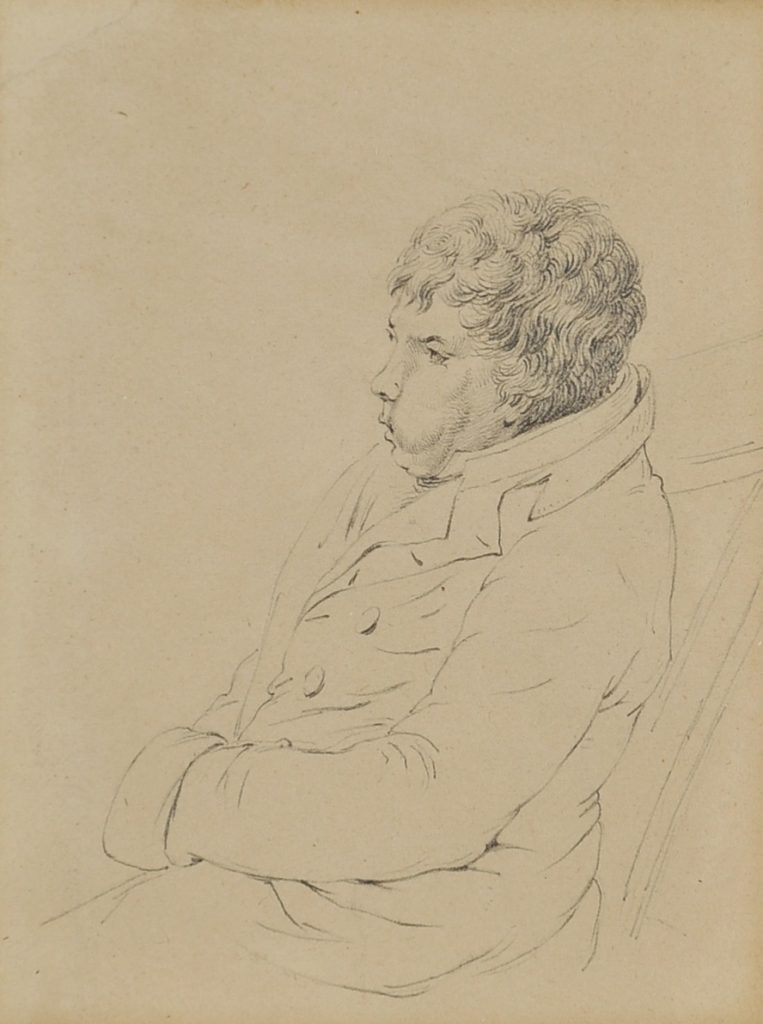

Sketch of David attributed to Georges Rouget, bequeathed to the Cleveland Museum of Art and sold at auction in 2009.

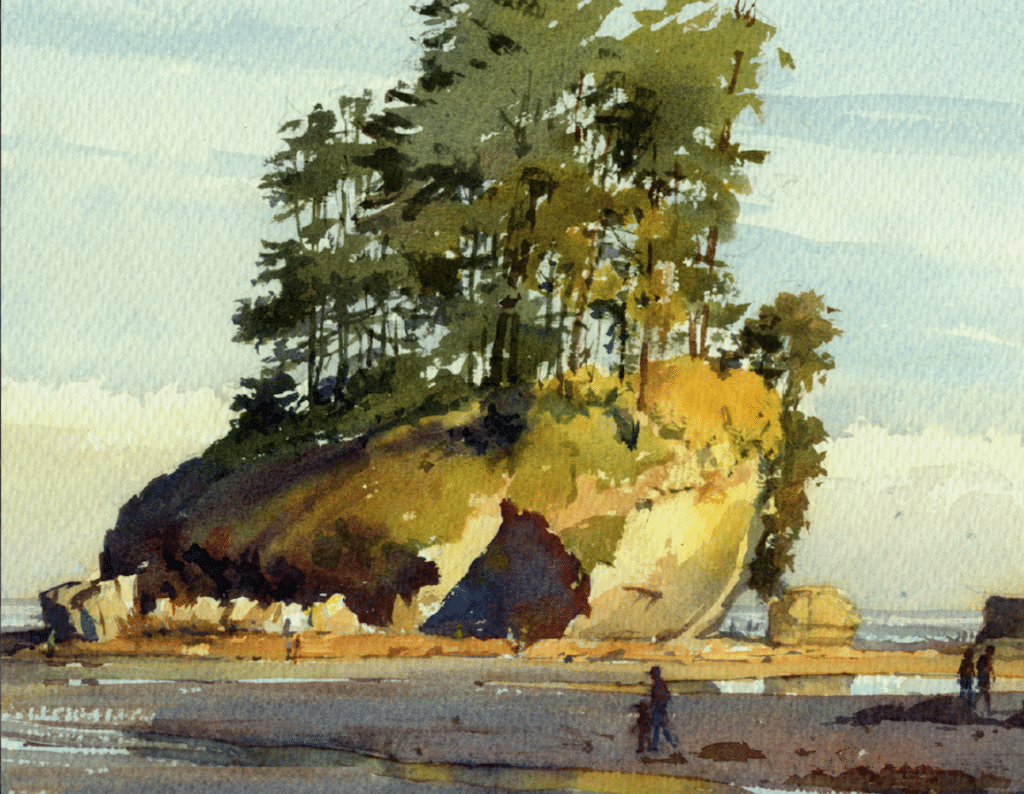

An Island in the Storm

Richard Sneary’s background as an architect and architectural illustrator helps him to use exceptional geometries of composition, light, color, contrast, form, abstraction, and detail to capture the sense of the places he paints and the unspoken stories they suggest.

Richard is one of the many master watercolorists serving as faculty during Watercolor Live, a three-day all-online immersion in learning from some of the top watercolor painters in the country, happening this weekend, January 26 – 28, 2023, with optional beginner’s day on January 25)

To register or to learn more, go here.