AArtists are fascinated by mermaids. That’s the conclusion you have to come to as soon as you scratch the surface of the proliferation of mermaids in art.

Gaston Hoffmann, (1883 – ?), Mermaid, 1926

Perhaps the hybrid figures fascinate so because subconsciously they represent the ability to live in two realms – artists, like mermaids, inhabit two worlds, one the solid ground of objective reality and the other pure feeling, the underwater realm of dreams and the unconscious, one reality and the other imagination, one visible and one invisible to anyone else.

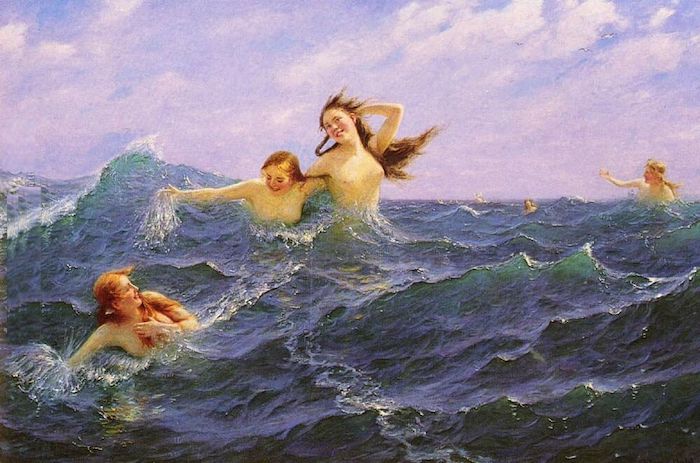

Ilya Repin, Underwater Kingdom, 1876

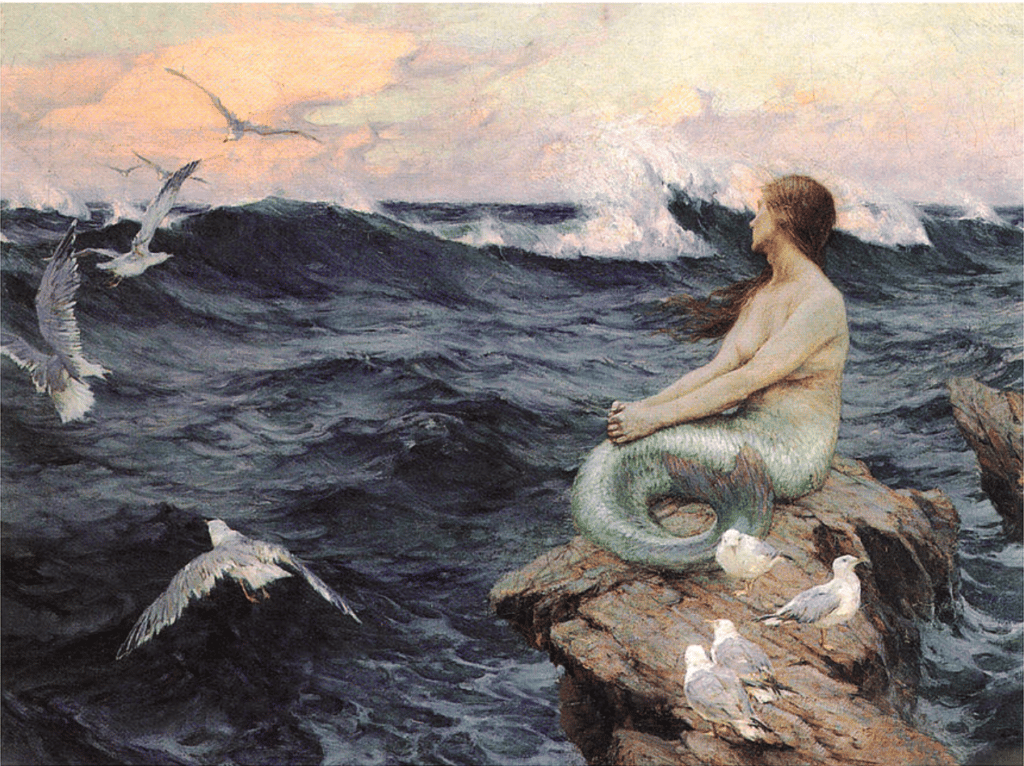

Perhaps that’s also why mermaids, unlike sirens, are often depicted not in groups but alone, and often as rather melancholy. They’re caught between two worlds, in danger of falling in love with mortals who cannot join them (unless she sacrifices her eternal oceanic life). And so they spend their days alternately playing among the waves and sitting on lonely rocks watching the horizon for distant ships or wandering among the sunken gardens and dusky ballrooms of Poseidon’s deep-sea mansions.

Charles Murray Padday, A Mermaid

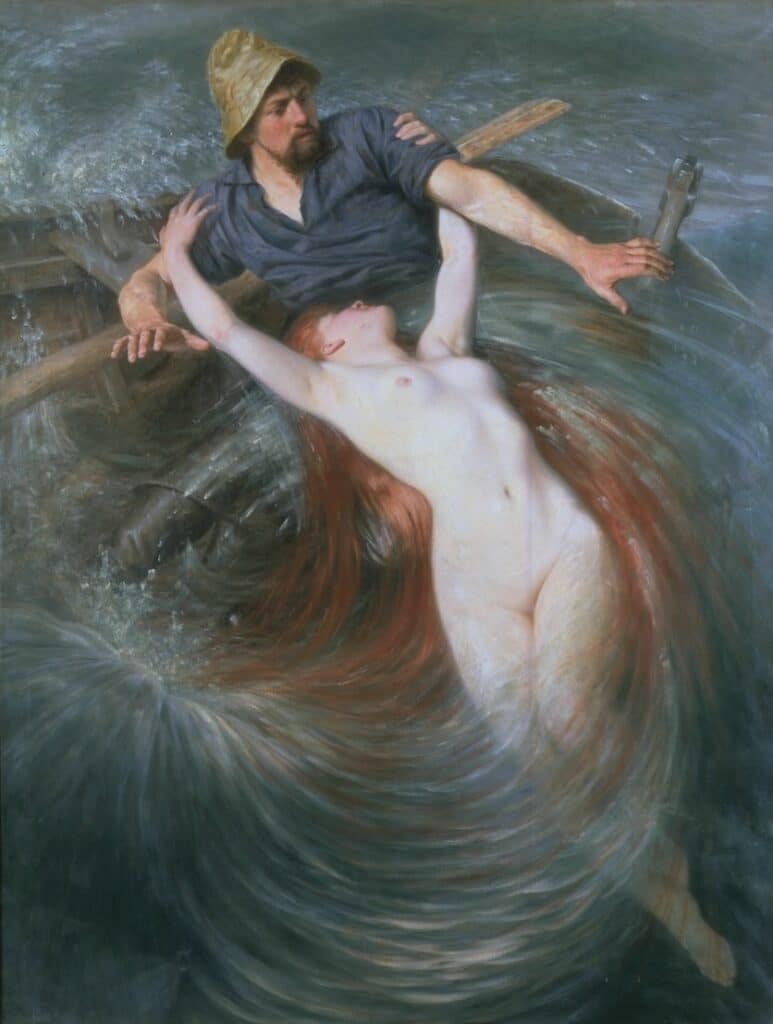

Or perhaps some classical artists saw themselves as the sailors instead: At the mercy of the elusive and capricious muse, in peril like the seamen they painted being lured by sirens to certain death or tempted by mermaids to follow beneath the waves.

Knut Ekwall, The Fisherman and the Siren

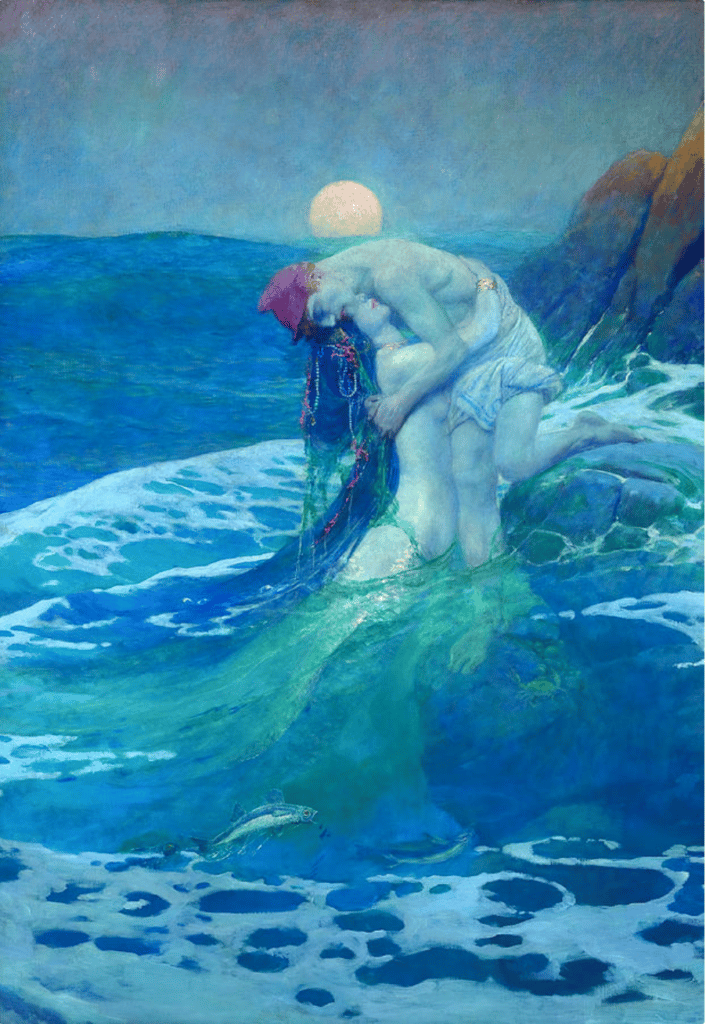

Howard Pyle, Mermaid

WhiteandBlueMountains has a really delightful slide show on YouTube of classic mermaid art set to “The Song of the Sirens” by Claude Debussy. Enjoy it here.

Hans Dahl, The Daughters of Ran

Life (for Mermaids) During Wartime

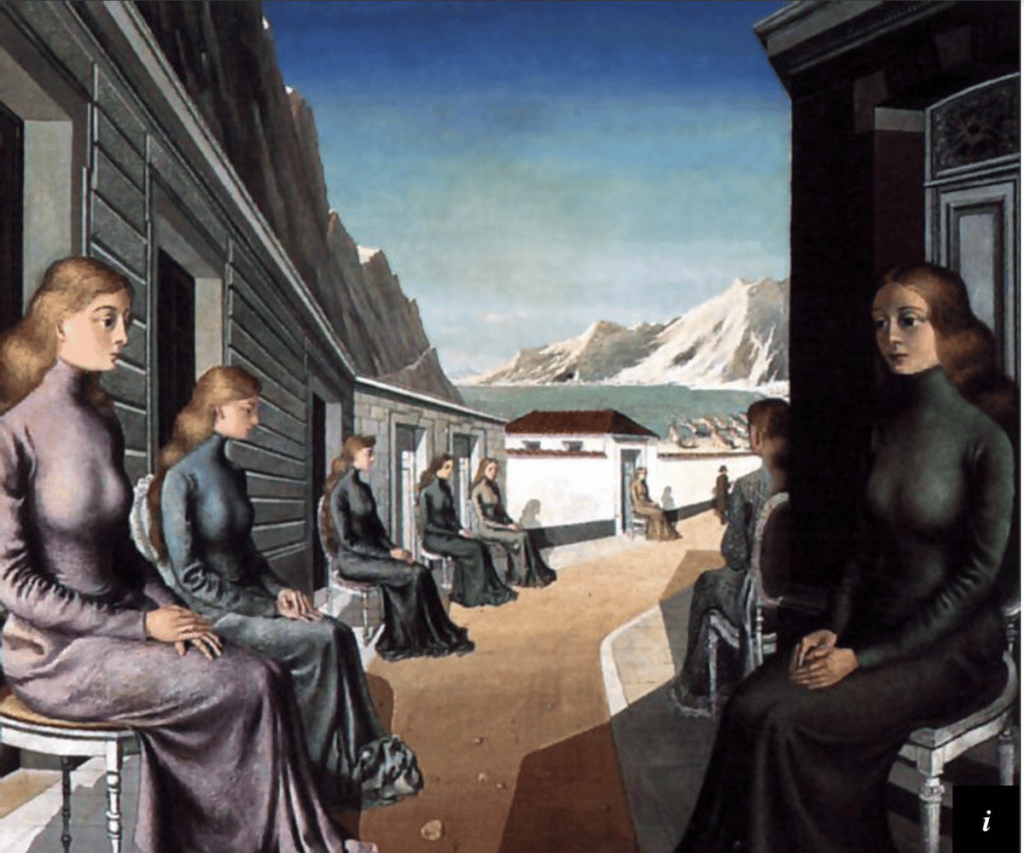

Paul Delvaux, The Village of Mermaids, 1942

Belgian painter Paul Delvaux put surrealism to good purpose in his 1942 painting The Village of Mermaids. It’s a mysterious painting, but we needn’t guess at its mood – it’s ominous and chilling. This world is frozen; the airless chill like that of marshal law emanates from the ordered row of identically seated long-haired figures, the icy-looking sea and glacial mountains, the deep shadows and somber color palette.

If we take the artist at his word, this is a village of mermaids. If so they look like they’re being treated as prisoners in lockdown, immobilized in front of their cells, prevented from reaching the sea in the distance, kept in line perhaps by the male figure walking away from us into the distance. They’re solemn, subdued, dressed the same in clinging gray gowns from chin to toe (fin?), with downcast, hopeless gaze.

Meanwhile, barely visible in tiny digital reproductions, the same women, now set free as half-naked mermaids, stream across a glistening beach toward a final disappearance into the green transparent sea. Many have seen it as allegory of wartime: the old life was a fairytale, whimsical and carefree, and now it’s anything but.

Surrealist paintings, like dreams, are composed of fragments of real experience transformed and reconfigured into surprising and elusive combinations. Paired with the foreboding mood, the surrealism of this painting works, as in the poem below by Lisel Mueller, to evoke the way nothing makes sense in times of turmoil, the way the world turns upside down, smothering life in confusion and incomprehensibility.

Born in Germany, the poet Mueller had a very personal reference for this work. Her family fled the Nazi regime, and she arrived in the U.S. in 1939 at the age of 15. She worked as a literary critic and taught at the University of Chicago, Elmhurst College and Goddard College. And yet, just like painting, Mueller’s poem asks more questions than it answers.

Here is the poem:

Paul Delvaux: The Village of the Mermaids

Oil on canvas, 1942

Who is that man in black, walking

away from us into the distance?

The painter, they say, took a long time

finding his vision of the world.

The mermaids, if that is what they are

under their full-length skirts,

sit facing each other

all down the street, more of an alley,

in front of their gray row houses.

They all look the same, like a fair-haired

order of nuns, or like prostitutes

with chaste, identical faces.

How calm they are, with their vacant eyes,

their hands in laps that betray nothing.

Only one has scales on her dusky dress.

It is 1942; it is Europe,

and nothing fits. The one familiar figure

is the man in black approaching the sea,

and he is small and walking away from us.

-Lisel Mueller

Mueller’s writing is available on Amazon

The artist Paul Delvaux said the painting was inspired by a dream. He explains everything about this painting, from what’s in it to what it means, in a letter to the Art Institute of Chicago which owns it, as showcased in this brief radio piece online here.

In the paint,

Chris