Ogunquit, a little town on the southern Maine coast – not famous Monhegan – was once the thriving epicenter of plein air painting in America.

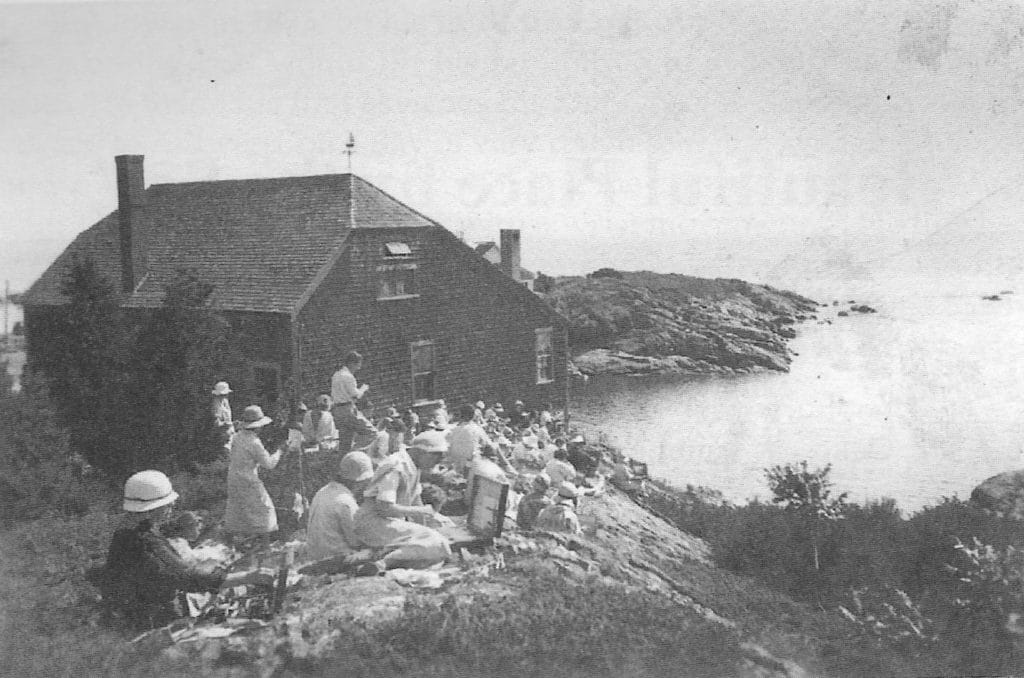

Charles Woodbury teaching his plein air painting class in Ogunquit, c. 1900

During the early decades of the 20th century, quaint Ogunquit emerged as a magnet for artists and creative spirits of many stripes.

John Joseph Enneking, Oqunquit

The name means “beautiful place by the sea” in the language of the Abenaki peoples, a language under threat of disappearing today. (The majority of Abenaki migrated to northern New Hampshire, Vermont and French-owned Canada after their Maine homeland was decimated by English colonization, disease, warfare, and enslavement beginning in the late 1600s so that Ogunquit could become a shipbuilding port for the British Crown.)

Vintage postcard from Ogunquit, Maine

In 1895, when Charles Woodbury, fresh out of college in Massachusetts visited, Ogunquit was a sleepy fishing village of rough-hewn fish shacks and rock-cliffs tumbling into the Atlantic – and all a stone’s throw from Boston. Woodbury seized on the pastoral farmland and rocky shores in his quest to create a truly American style of painting.

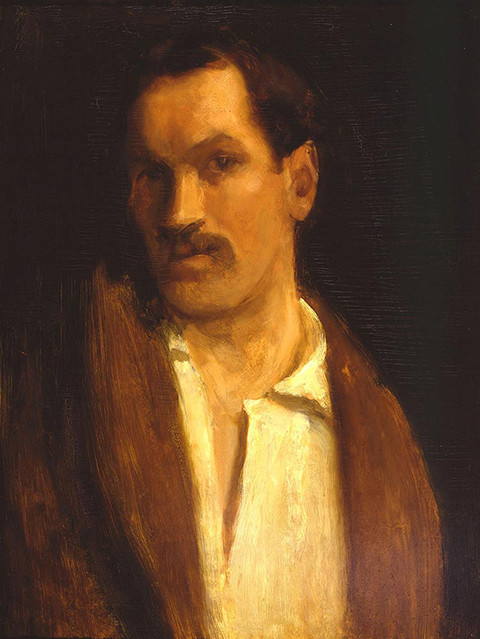

Charles Woodbury, soon after establishing his summer painting school in Ogunquit in 1898

The artist purchased an old cow pasture overlooking the ocean for next to nothing from a puzzled local and proceeded to establish it as an outdoor painter’s paradise. First a friend or two for a couple weeks away from the big city, then more and more painters would join him.

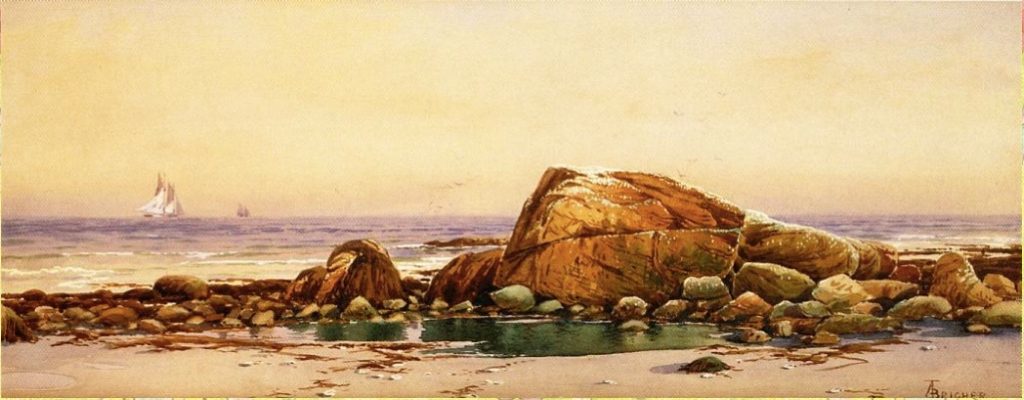

Alfred Thompson Bricher, Ogunquit

“As they watched the poetry of fishermen and their small dories, streams that quietly meandered around hay fields and surf that glistened and pounded the rocky shore, those first artists rendered romantic scenes that inspired others to see what they were painting about,” wrote colony chronicler Louse Tragard in A century of Color. 1886 – 1986: Ogunquit Maine’s Art Colony, the definitive illustrated history of the art colony. “Soon word of this poetic scene spread and more and more people wanted to experience what the artists saw.”

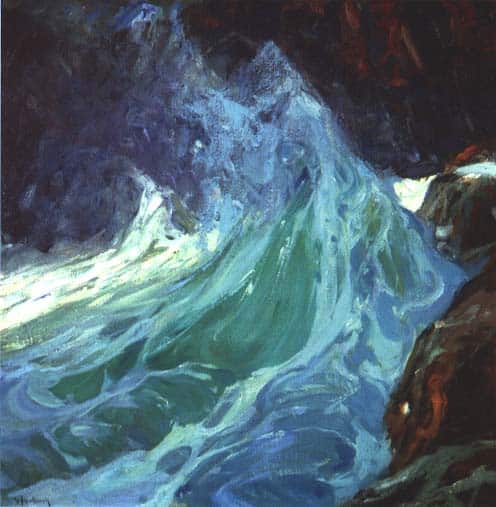

Charles Woodbury, Deco Wave (Dancing Wave) 1914

Each summer saw the arrival of more artists unknown and known, among them Marsden Hartley, Edward Hopper, George Bellows, Robert Henri, John Joseph Enneking, and Emil Carlsen. Soon a rich camaraderie of fellow creative spirits began to grow; locals would rent out cheap rooms or parts of their barns to the descending “artist types” and creativity and tales of crazy exploits ensued.

“Great friendships and fun grew between the artists, locals, and now more frequent city summer visitors who began to buy the artists’ works and/or attend emerging summer art schools,” wrote Tragard. “Ogunquit began to provide big city artists with a summer respite filled with inspiration and a unique social life.”

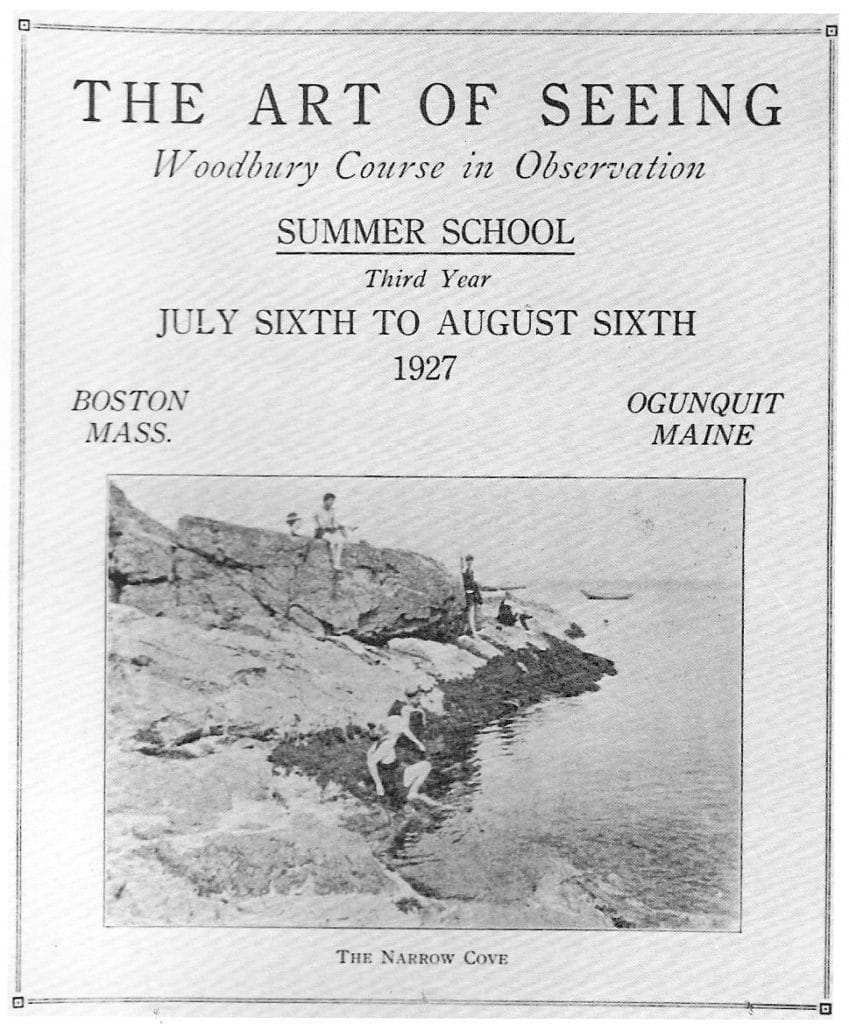

When Woodbury opened his school in July, 1898, its popularity exploded – his outdoor seaside classes literally left the traditional classical art academy in the dust.

High Tide, Narrow Cove, Ogunquit, Maine” by Charles Woodbury, 1939. Courtesy of Vose Galleries

Woodbury established the country’s first outdoor painting school (Charles Hawthorne usually gets the credit for that – but Hawthorne opened his outdoor school in Provincetown in 1899). For the next 40 years, Woodbury taught the “art of seeing,” emphasizing observation, subjectivity, and expression in art – how to paint the way things “seem,” not just how they appear.

This was quite revolutionary for the time, though it’s largely how most artists teach plein air painting today.

Woodbury famously advised his students to “paint in verbs not in nouns.” He wanted his students to enter into the life of the things they painted, to inspire them to fresh, “active” seeing and expressive creativity. “You don’t draw what you see of the wave – you draw what it does!” he would tell his students.”

Surrounded daily by the sea, Woodbury became a marine painter of national importance, and thousands attended the lively summer art school. “As new art trends emerged, they too found their expressions in Ogunquit’s craggy coastline, bustling cove life and casual ambiance,” writes Tragard. “People here cared less how you looked or dressed and how you adhered to social mores… A rich cultural scene fostered even more creative expressions.”

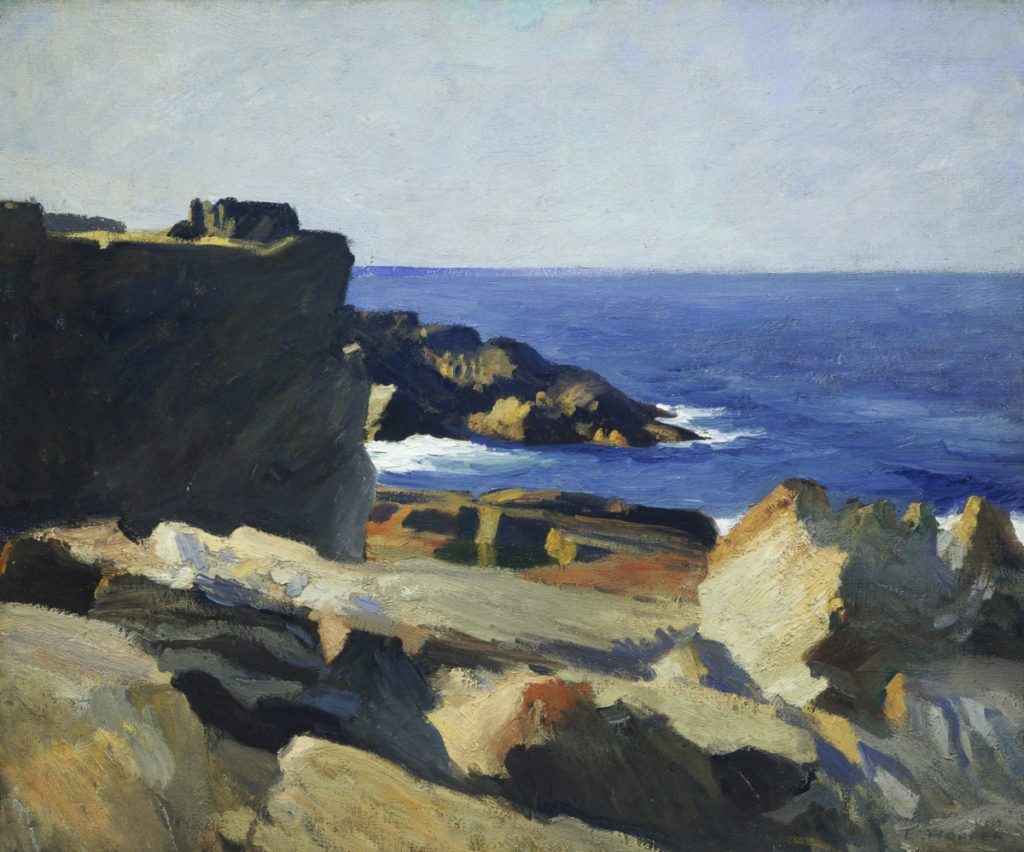

Edward Hopper, Square Rock, Ogunquit, 1914-1919

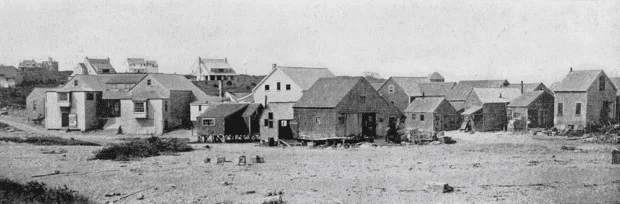

European modernism with a New York flavor came and thrived alongside the plein air school. In the summer of 1902, Hamilton Easter Field – along with his protege Robert Laurent (who would eventually become a sculptor and was 12 years of age at the time) – arrived in Ogunquit looking for a summer residence. Instead, Field bought a row of shacks that he started renting out cheap to artists. Field’s little enclave of live-in studios was a major step towards creating a true artist colony.

Field’s studio is in the far left; these houses are similar to (if not the actual) structures he rented out to up-and-coming artists.

A dedicated Modernist, Field founded his own summer “graphic arts” school in Ogunquit 1911. He and his students preferred live indoor models and studio work, whereas Woodbury’s students were out-of-doors. Literally opposite each other on spits of land separated by a channel of water, the two artists and their schools coexisted peacefully and the artistic community in Ogunquit thrived all the more.

“Self-Portrait” by Hamilton Easter Field, ca. 1898. Courtesy of Barn Gallery Associates, Ogunquit, Maine, USA

Another summer resident was modern artist Walt Kuhn, an organizer of the earth-shattering 1913 Armory Show that introduced European modern art and abstraction to the mainstream American audience.

In 1953, Henry Strater – a close friend of Ernest Hemmingway who’d first come to study with Field in 1919 – opened the Ogunquit Museum of American Art on a plot of land purchased from the Woodbury family. With a strong emphasis on contemporary art even today, the museum further spread awareness about modern American painting in the northeast.

“Today,” writes Louis Tragard, “though the scene has changed, there are still artists who find poetry in the landscape and want to keep the creative spirit alive. The cheap rooms and parts of barns are long gone, but the galleries and now the Ogunquit Summer School of Art (established in 2013) strive to help people see what is still all around them in this “beautiful place by the sea.”

As of 2022, the current Ogunquit Summer School of Art offers classes in drawing, studio and plein air oil painting. The current “colony” also organizes plein air workshops and “painting adventures” with a variety of instructors in beautiful locations such as Monhegan, Ireland, Italy, Paris, and Bermuda (word is winter can get a bit nippy for plein air painting on the Maine coast).

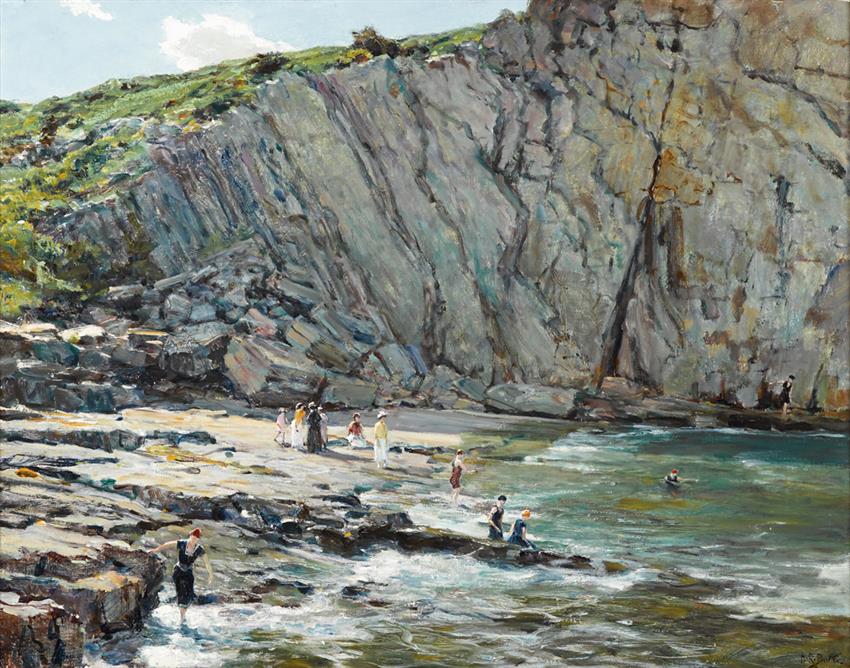

Emil Carlsen, Surf Breaking on Rocks (Bald Head Cliff, Ogunquit)

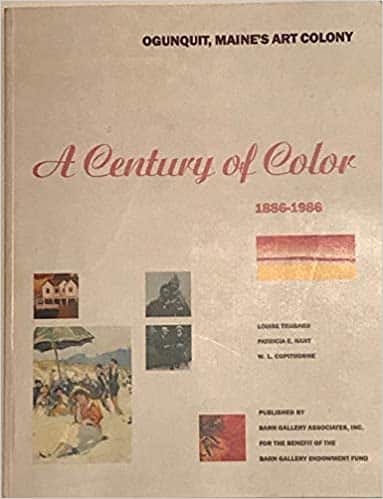

Note: Louise Tragard, whose writing is quoted in this article, is the author of A century of Color, 1886 – 1986: Ogunquit Maine’s Art Colony. (Available at the Ogunquit Museum of Art and Amazon.)

Painting the ocean from life seems intimidating – until you’ve done it a few times in front of your computer. If you’re ready to dive in, there are more than a dozen top-shelf teaching DVDs that immerse you in the techniques you need.