According to French proto-modernist Edouard Vuillard, in painting, “nothing is important save the spiritual state that enables one to “subjectify” one’s thoughts to a sensation and think only of the sensation, all the while searching for the means to express it.”

Edouard Vuillard, Large Interior with Six Persons (1897), Kunsthaus Zürich

Edouard Vuillard, In the Waiting Room

Edouard Vuillard, Woman in a Striped Dress Le corsage rayé (1895), National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Edouard Vuillard, Persons in an interior – Music (1896)

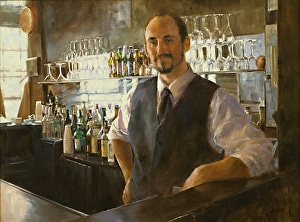

Susan Blackwood: MAPing is on the Menu

This painting by Susan Blackwood won a top award at the prestigious American Watercolor Association show.

Susan Blackwood is a Signature Member of the American Watercolor Society and the National Watercolor Society. She has painted en plein air (outdoors) in England, Wales, France, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Mexico, and China. Over 70 of her paintings have been reproduced by several companies and sold all over the U.S.A., Canada, Europe, England, and Australia as limited-edition prints and giclees.

So how does a career like Susan’s happen?

Susan Blackwood began with a burning desire to draw. In fact, in the very early years, the walls of her house became her crayon “canvas.” After that was shut down by her parents, she became a little more creative as she took her pencils and drew behind the curtains. That was only discovered when the curtains came down!

Susan’s parents were both artists. And later in life, when she traced her family tree, she discovered that she has family ties to Rembrandt. So, the love of art and the desire to create art run very deep in her family. This may explain the non-stop focus, passion, and drive to make art.

She has always had an intense level of curiosity. She says her favorite subjects are the ones right in front of her at any given time. Whether in real life or in photos, Susan can find the spark in almost anything she sees.

Take “gobs” of photos

Susan takes pictures all the time. She takes pictures of everything. “For me, it’s more ‘found’ things, like capturing the way a shadow falls from a tree,” she says.

She has specific tips on exactly how to use the camera to get the most interesting pictures (no matter what kind of phone or camera you have). She uses what the camera captures as a major (but not the only) source of inspiration.

MAPS

What sets her apart from most is that she has every brushstroke planned; she uses her own “MAPS” system. It stands for Making Artistic PlanS and it allows her to plan out a composition and move smoothly from nothing to completed work in a very short amount of time. Having a plan, she says, actually eliminates stress; it lightens your mind and allows you to just relax and paint.

In the beginning, she felt resistance from some artists to the idea of putting some structure on an act so creative. But in a short time, those same artists became raving fans of her MAPS system. The increase in speed is not at all because of shortcuts or lower quality. In fact, the paintings created under this system tend to be higher quality, with fewer mistakes. They have better design cohesion. They are the kinds of paintings an artist can build a reputation on.

Blackwood explains and demonstrates her MAPS system in the video, Simple Watercolor Secrets (Using the MAPS System).