John Singer Sargent’s little-known, seemingly minor painting, Two Wineglasses is a gorgeous little plein air masterpiece.

When I first saw a picture of this painting (I haven’t seen it in person), I got that catch in the chest only work that really speaks to me gives. I had to ask myself why (heck, I mean, it’s just a painting of an empty table!). What is it about this painting that does it for me? This is Sargent, so no surprise, it’s the light. But specifically, I believe the light in this one conveys a subtle sense of excitement. Sargent makes an everyday scene sparkle and shine.

And there’s something deeper to it too, that’s not just about technique. In setting the ordinary world shimmering and glowing, a painting like this gives you that same feeling you have, from time to time, of being fully alive to your existence, when for whatever reason the dross of everyday routine falls away however briefly, and life for an instant brims with possibility and pizzazz.

Here’s how, in Two Wineglasses, Sargent has insured we experience a scene flecked with light. He’s dabbed little staccato brushstrokes of high-keyed pigment throughout the picture, but they are especially visible in the warm white shards of paint, like pieces of sky that have detached themselves, dancing through the leaves and falling in pools and streaks onto the tabletop and from there to the patio floor like animated confetti.

Dancing flecks and symphonies of light and shadow!

(When people talk about Sargent’s use of light, that’s what they mean; things like that and the sort of mini symphony of vibrating warm and cool tangerines and violet grays he orchestrates on the table – light that simultaneously 1. directly falls on 2. indirectly fills the shadows across and 3. passes through the white tablecloth!)

Finally you notice the foreground and the two wineglasses on a tray and remember the title. Only then do you fully realize this is an outdoor cafe, seen early, before the afternoon crowds fill it up, perhaps from the server’s point of view.

You might think, then, of things we associate with outdoor cafes – the sparkle of conversation, lovers, perhaps on a first or second date, sparks flying between them, or on the contrary, longtime companions at ease in each others’ presence, more akin to the wash of the sunlight across patio floor or the ambient glow, like warm coals, of sunlight filtering through the linen table cloth. Rather like Renoir in The Luncheon of the Boating Party (https://www.phillipscollection.org/collection/luncheon-boating-party), Sargent portrays the world of the leisure classes, only with far more subtlety and poetry – the wine glasses, because there are two, act as stand-ins for all the celebratory togetherness and delights of the good life to be enjoyed here.

Everything about this picture radiates unencumbered, unhurried contentment. The pleasant outdoor setting is that rare place apart, where outside and inside, the natural and the civilized, mingle in blissful equilibrium. The lush vegetation is picturesquely casual and unkempt, suggesting unfussy hospitality. The slats in the fencing are soft-fuzzy sketches, a permeable boundary between inside dwelling and the outdoors. Any potential severity in the squared column in the center dissipates, soothed by Sargent’s brush into indistinct background.

Design: Using light, shadow, and directional lines to guide the eye through the composition

Design Design Design

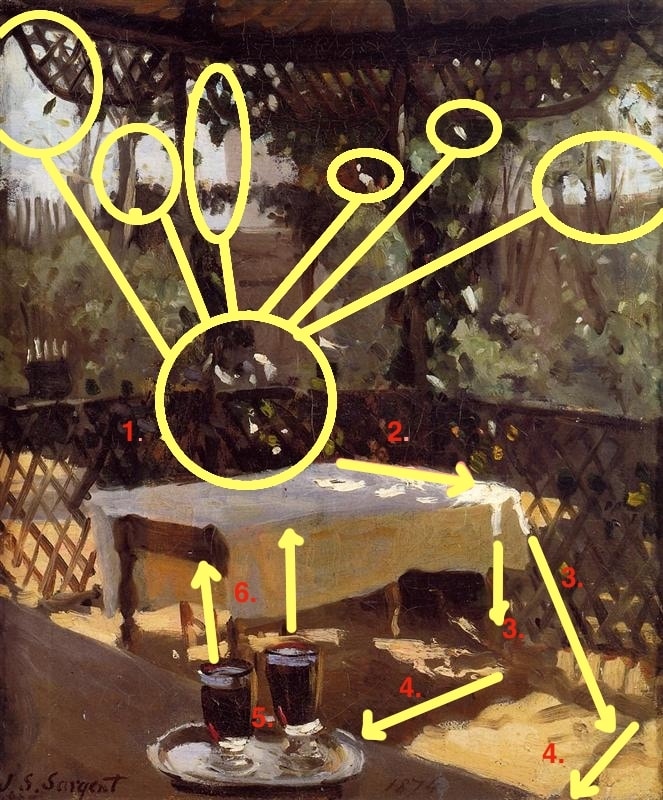

Let’s consider the design – not just for its own sake, but for how Sargent uses it to support our reading of the painting. Where does the eye go? For me, it goes straight to that lively dance of light among the shadows of the vines and the table. We tend to notice areas of the greatest contrast and the hardest edges first: Sargent’s darkest darks and lightest lights all come together there (specifically, in the three dots of light hovering in formation above the table, where the hardest-edged and lightest flecks of light pigment blaze up against the largest and densest single mass of dark violet-black – see #1 in the overlay).

From there, the eye is pulled in two directions – up toward the other bits of light in the leaves and down/across (#2 in the diagram), following the angle of the table’s edge, toward the thick chunk of warm-white sunlight striking the tablecloth’s edges, which point us down (see the two #3s) toward diagonal lines on the floor (the two #4s).

Where do our eyes go next? For me, it’s to the wineglasses, rapidly conducted there by those strongly connective lines of shadow on the floor (the two #4s). The wine glasses themselves (#5) create a strong vertical thrust, bolstered by other nearby vertical elements (#6), so my gaze travels back up into the areas of leaf-shadow and light to start the circuit over again.

Now, I’m not saying that Sargent necessarily thought all of this through, but in terms of metaphor, I note that I have traveled through a harmony of wild nature (loose light in the dark leaves) and sophisticated culture (cafe’s white tablecloth) to arrive at the wine, itself a union of nature and culture created for the purpose of giving pleasure. This isn’t in the painting – but neither is it entirely in my head or coming out of nowhere. This is what was just under the surface of my initial enjoyment of the painting. By trying to put words to it, I’m reading my own meaning into the work, but then again, Sargent’s rich and resonant imagery invites me to it. Great painting can be everything and nothing – a subtle disquisition on human experience – and just an empty, un-made table in the corner of a common cafe.

For me, that’s the miracle of art, especially art that gives us the sudden set-ablaze-of-the-everyday. It reminds us that if we can only clear our senses of the overly familiar we can really see – and a life more fully lived is possible.

If you’re looking for ways to get more light into your paintings, a wide variety of instructional videos by numerous popular masters are available that can show you how.

Pray It Doesn’t Sink – Take Pix in Case It Does

Alejandro Merizalde, from his new book, 100 Churches

Venice has captivated the imagination of artists and romantics for centuries, and during that time, its architects and stonemasons have constructed more than 100 places of worship. Photographer Alejandro Merizalde has been working in the city (now being threatened by seawater rise) since 2008, taking pictures for a photo book just out, called 100 Churches of Venice and the Lagoon. Merizalde’s lush volume documents many the city’s most elaborate and beautiful buildings — most of them Catholic churches, but also two synagogues and one Anglican church.