Johannes Vermeer’s The Art of Painting (c.1668) invites us to see in his work much more than consummate skill and flawless technique for capturing diffuse light from an unseen window (though … THERE’S THAT!).

Johannes Vermeer, The Art of Painting

Check out the tapestry hanging along the left side of the painting. It’s been drawn aside like the curtain in a theater. This repoussoir does more than beckon attention into the work; its reference to theater and drama subtly announces that this is no randomly observed domestic setting but a carefully composed “stage” laden with story and meaning. What’s more, the meaning relates to the creative arts, for this is The Art of Painting also called The Allegory of Painting and The Painter in his Studio, and it is packed with meaningful details.

Vermeer shows us an artist (himself?) painting a “muse,” a mythical goddess of creative inspiration, or else an allegorical figure such as “Fame,” “Painting,” or “The Spirit of Art.” He’s outfitted the model with allegorical symbols – besides what I take to be the blue painter’s smock, she wears a crown of laurel leaves (classical symbol of valorous achievement). She holds a book in one hand and a brass instrument in the other, the latter either in reference to music or to fame (that is if, as some do, we take the figure’s close resemblance to Clio, the Muse of History as described in a then-current manual for artists, as the true subject).

There’s a plaster mask on the table, such as artists used for drawing, which might also symbolize sculpture (and/or the debate-of-the-day over which was the nobler art, the sculptor’s or the painter’s). In addition, the presence of a piece of cloth, a folio, and some leather on the table have been linked to the symbols of the Liberal Arts.

On the wall hangs a large map of the Netherlands. Art historians have noted that a crease neatly divides the Seventeen Provinces into the north and south, likely to symbolize the division between the Dutch Republic to the north and the provinces to the south that were then under Austrian Habsburg rule. This interpretation might have appealed to Hitler, who owned the painting during World War II.

High res detail of the map (barely) showing the allegorical figures in the upper left corner.

Throughout his work, Vermeer uses such intricate details not for their own sake but to carry suggestions of meaning. The map on the wall is even decorated with its own allegorical figures, including in the upper lefthand corner, one bearing a cross-staff and compass, the other a palette, brush, and a city view (so small they’re not even visible online).

Adding all these elements up, this is about linking the virtues of painting to grander ideas of fame, nationalism, human achievement, and history. The Art of Painting then is an emphatic celebration of the artist’s talents and worth.

Vermeer never sold this work, so it’s thought he considered it a sort of record of his own achievement as well as a kind of showpiece of his sophistication and virtuosity as an artist – something that couldn’t fail to impress visiting patrons.

Art historian Walter Liedtke praised this painting “as a virtuoso display of the artist’s power of invention and execution, staged in an imaginary version of his studio …” and according to critic Albert Blankert, “No other painting so flawlessly integrates naturalistic technique, brightly illuminated space, and a complexly integrated composition….” – along with, I might add, such a rich and mysterious poetry of potential meaning(s).

And so – huzzah for the art of painting!

By the way, contemporary painter Virgil Eliott breaks down Vermeer’s style in his how-to video on traditional painting techniques.

Did Andrew Wyeth Fake His Own Death?

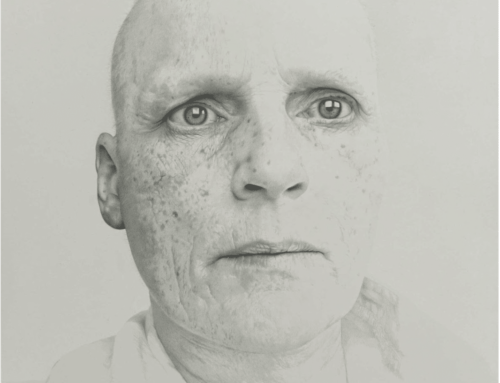

Andrew Wyeth’s drawing of his own funeral.

No, that was just clickbait, and I apologize. But in fact he DID paint it! And a new exhibition in Waterville, Maine, at the Colby College Museum of Art, Andrew Wyeth: Life and Death, is offering the first public presentation of a recently rediscovered series of drawings in which Wyeth imagined his own funeral in stark detail. Just goes to show you can paint quite realistic and detailed work without having to work from, er, life. Through October 16, 2022.