Ejnar Nielsen sometimes gets put into the same category as Edvard Munch. Both were northern European, turn-of-the-century painters in the Symbolist mode exploring somber themes of life, death, and the feeling of loneliness.

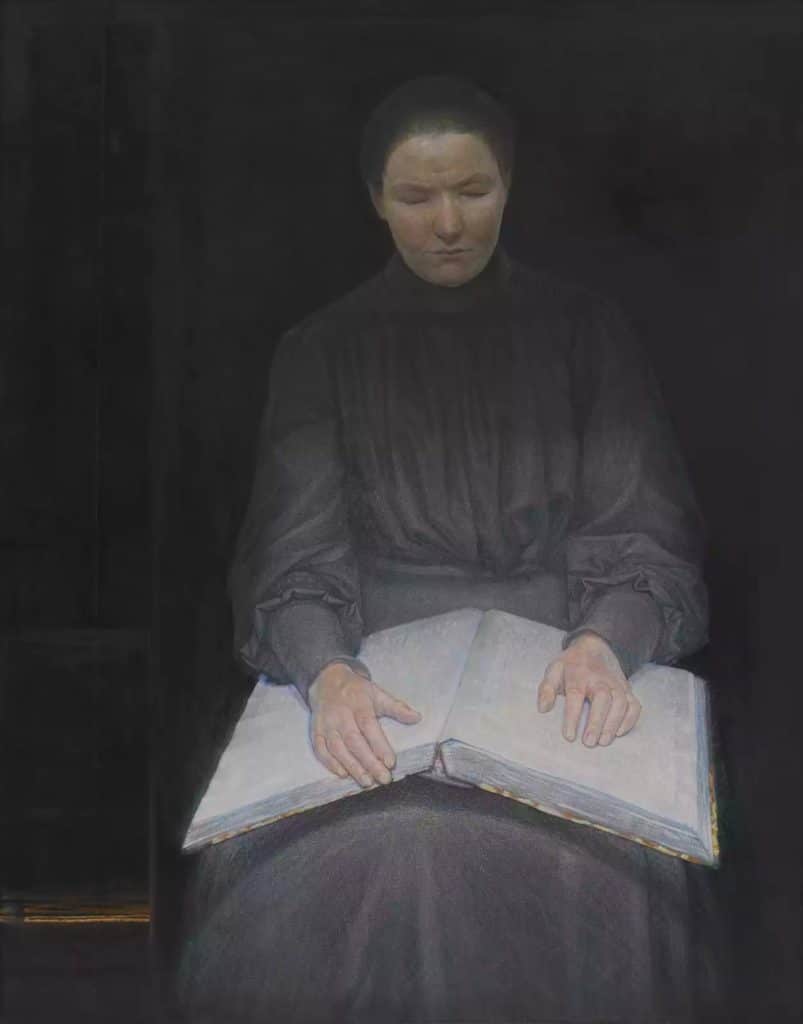

Ejnar Nielsen, A Blind Girl Reading. Oil on canvas, 1905.

Nielsen differs from Munch in his realism. Most Symbolists felt that for painting to present strong (sometimes extreme) psychological states and ideas, the artist should not be slave to the objective, quasi-scientific representational approach exemplified by Realism and Impressionism.

Nielsen, as other Symbolists did, stylized parts of his paintings and loaded them with symbolic significance. However, instead of rejecting Realism, he clearly doubled down on it, at least he did so in A Blind Girl Reading, the 1905 painting reproduced above.

The symbolism in A Blind Girl Reading, is embedded, not obvious, and it works on an emotional, not an intellectual level: we feel this woman, we sense her separation from the exterior world, and we intuit her interior life.

Wrapped in gray, featureless clothing, she sits head down and eyes closed, nearly enveloped in the literal darkness of a lightless room. A weak strip of light showing beneath the closed door behind her further emphasizes the dark. Everything suggests the shuttering of the woman’s visible world – except for the book, which seems almost to be luminous, to emit its own light, as she runs her hand across the braille.

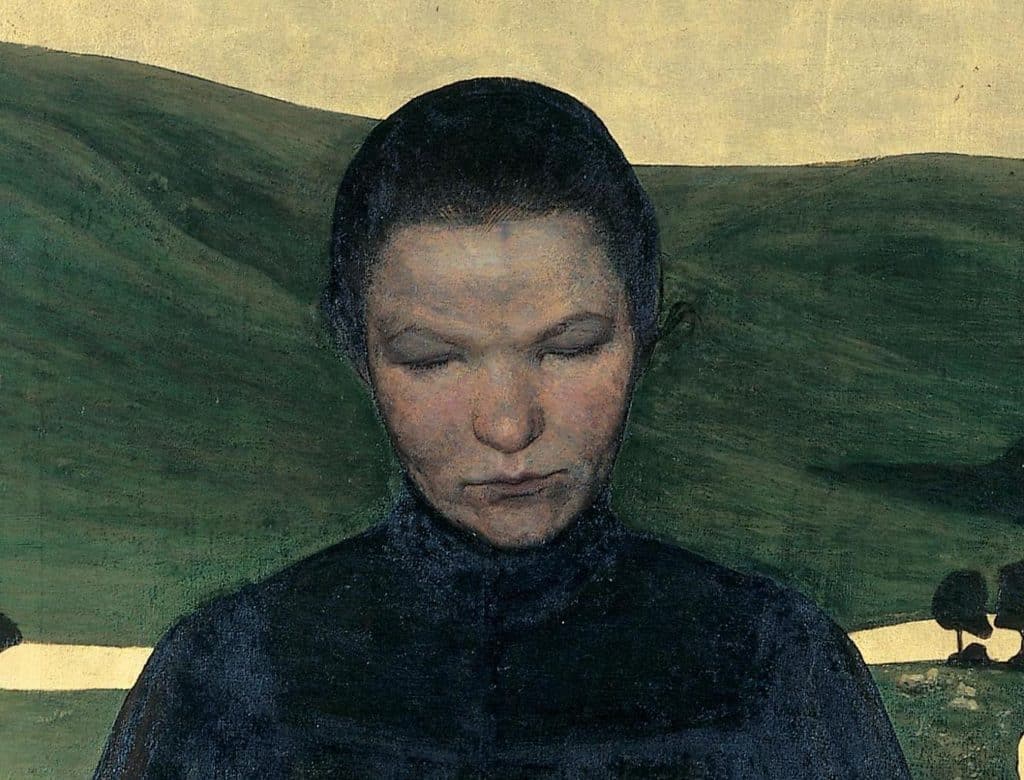

“The embossed book, which is built up in layers of green and white paint, is the most thickly painted area of the canvas and the text the girl touches merges into the medium of paint,” notes scholar Heather Tilley (“Portraying Blindness: Nineteenth-Century Images of Tactile Reading” in Disability Studies Quarterly.) “Crucially, it is the raised-print book that radiates the most light, challenging traditional associations of sight with knowledge.”

Detail of the book in braille from Ejnar Nielsen’s A Blind Girl Reading.

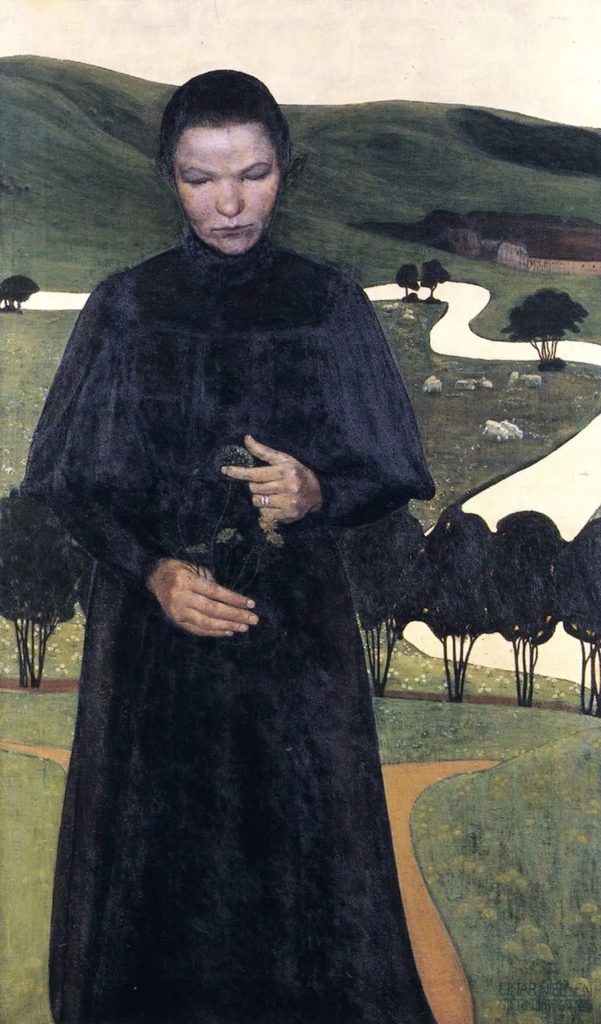

It seems to me Nielsen engaged the same sense of the tactile when 10 years earlier he painted the blind woman standing in a strangely luminous Symbolist landscape gently touching, this time, some wildflowers, primarily a dandelion.

Ejnar Nielsen, The Blind Girl (1896-98)

In this painting, the contrast is striking, between the stylized landscape and the realistic handling of the figure. The landscape is shown in two-dimensions, as if unreal, the almost hidden walking path lined only with faded, out-of-focus dandelions; the version in the blind girl’s hand is far more detailed and realistic, again emphasizing the split between inner knowing and the outside world.

As soon as I stumbled upon a pairing of this painting with a photograph – also of an apparently blind woman exploring a dandelion by touch set against a background of neatly trimmed trees – I wanted to get at the story behind the artist and the model and how these paintings came to be.

However, the website hosting the photo was in Danish, which neither I nor Google Translator can read. Which is just as well.

Part of what made me want to know who the girl was, I think, is how specifically and intimately Nielsen saw and painted her; you almost feel you’re in the same room with her. Perhaps her closed eyes engage our viewing in a way different from typical portraits. But what’s intriguing is surely something other than the facts of the case, the names of the people and the places involved.

But what really moves us to wonder, at least in part, is the work’s slippery combination of observational painting and symbolism and the overall strange energy of these ultimately unexplainable works of art.

Still, one can’t help dwelling on the encounter between a sensitive young woman deprived of sight and a painter so preoccupied with the processes of artistic seeing. Nielsen apparently lived somewhere between the two realms, as many artists do – seeing past the surface of the outside world, while bringing forth the creative vision within.

There are so many ways to “tell stories” in painting. Get started with the DVD Storypainting: Creating Emotion with Your Brush by in-demand artist Nicholas Coleman.

Attention Getter!

Thomas Moran, Fort George Island, oil, 11 x 16 inches, 1880

After yesterday’s post, First Get the Viewer’s Attention, several readers took up the challenge to send in images and ideas about paintings that pull you in from across the room.

David G. sent an image of Thomas Moran’s 1880 landscape Fort George Island. This one is such a stunner in person that he never forgot its impact.

“Years ago I saw it in an exhibition in the Florida State History Museum in Tallahassee, Florida,” he wrote. ” Although not a large painting (it’s only 11 x 16 inches), from across the room it dominated all the other paintings in the exhibition.”

A site of human occupation for over 5,000 years, Native Americans feasted here, colonists in 1736 built a fort to defend Georgia, and the one-percenters of the 1920s came for vacations. There’s a state part there now.

If you have more ideas (images not necessary) for paintings whose power is in their immediate impact, please email them to me!